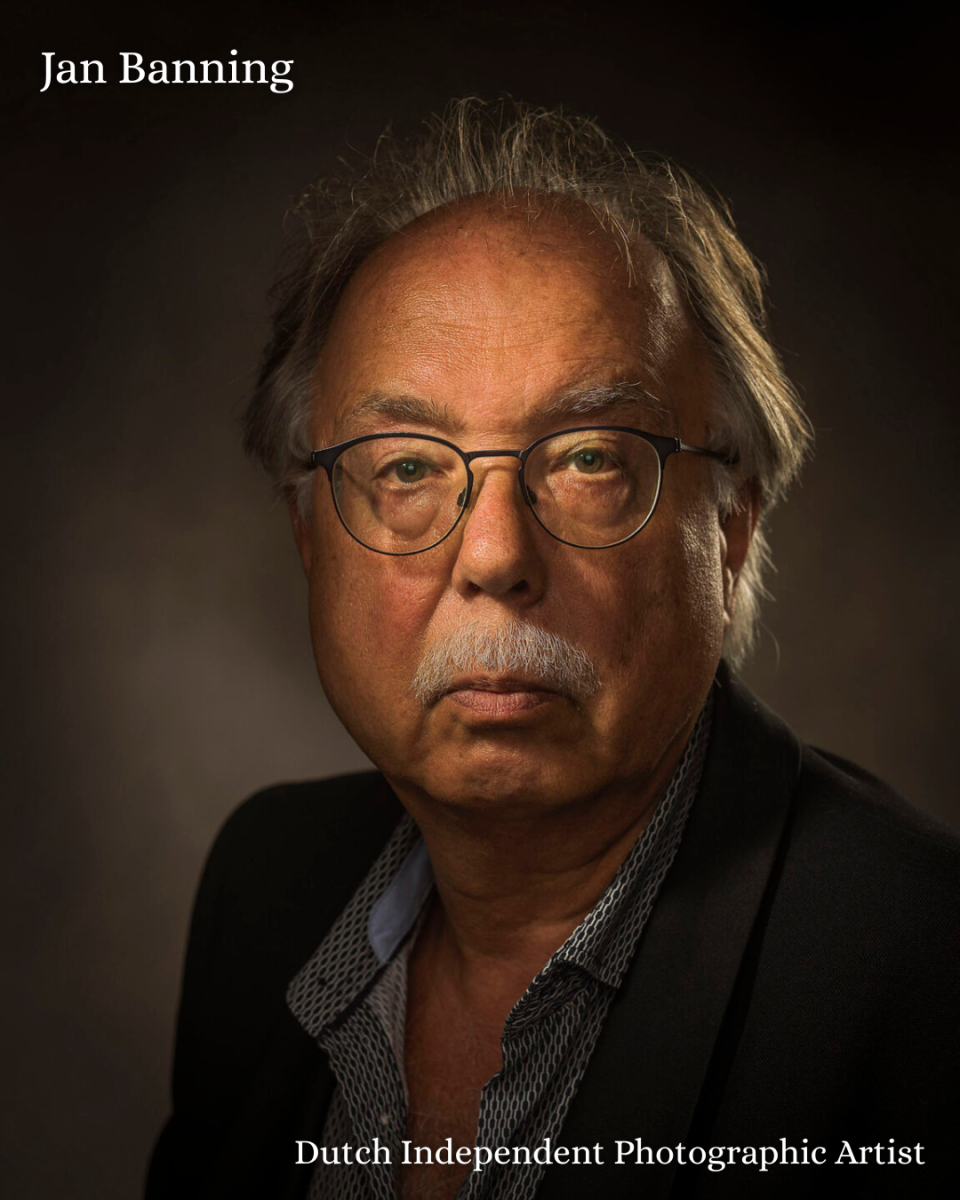

Dutch photographer Jan Banning paid a visit to Suffolk University Oct. 21 and brought his perspective on power, justice and human dignity to the Ford Hall Forum event titled “Photography, Art and Activism.” The discussion was moderated by Kevin Carragee, Suffolk University former research professor of communication, journalism and media.

The event was opened by Susan Spurlock, the executive director of Ford Hall Forum, the nation’s oldest continuously operating free public lecture series. Located in the Sawyer Library Poetry Center, the Ford Hall Forum has promoted free speech, civic dialogue and open debate on issues that shape the world. It promotes engagement among Suffolk students t and broadens their knowledge of worldly topics, such as Banning’s expansive and diverse body of work.

“Jan Banning’s work bridges art, journalism and social activism,” said Spurlock. “His images invite us not only to see, but to question and to bear witness.”

Carragee introduced Banning as a distinguished photographer and close friend whose art combines aesthetics with advocacy. Quoting Czech writer Milan Kundera, Carragee noted, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” He says Banning’s photographs are like a visual form of remembrance, depicting survivors and victims of oppression whose stories might otherwise be unheard by the public.

Banning’s career has spanned several decades and continents. His projects have included many different subjects, such as portraits of Rwandan genocide survivors, as depicted in his series Reconciliation, in which survivors joined with the killers of their loved ones and found peace despite the violence of their past.

Another project of Banning’s highlighted at the event was Comfort Women – which showed 18 Indonesian women out of the thousands across Asia that were enslaved by the Japanese military during World War II. These women were subjected to sexual abuse and violence, and bravely stepped up to tell their stories with the help of Banning.

Banning then went on to share how his parents’ history under Japanese occupation in the Dutch East Indies has shaped his worldview.

“My parents were locked up in internment camps,” said Banning. “There was exploitation, hunger and disease, but they talked about it openly. That openness influenced the way I look at the world.”

Despite his impressive work, Banning never studied photography in the formal way. He attended the Radboud University of Nijmegen, where he studied social and economic history. He says this knowledge taught him to research thoroughly and contextualize every project.

“I was a lousy photographer when I started,” said Banning. “But history taught me how to investigate — and that’s what drives my work.”

Over time, Banning’s photography shifted to what he refers to as “artivism”— a combination of art and activism.

“I realized publishing a photo once isn’t enough,” said Banning. “What’s published today is often forgotten tomorrow. Exhibitions help keep the work alive and part of the public conversation.”

Banning then shared images from his acclaimed series Bureaucratics, which shows civil servants seated behind their desks in eight different countries, including India, Bolivia and France. Each photograph is composed to emphasize the monotony of bureaucratic systems.

“I chose the most boring square composition possible,” said Banning. “Bureaucracy itself is rigid, full of rectangles and rules. The person in the center represents the human element within that system.”

Carragee noted that Banning’s work challenges both power and perception.

“Empathy defines Jan’s way of seeing,” said Caragee. “His images don’t sensationalize suffering. They ask viewers to remember and to care.”

The event then turned to a discussion of Banning’s book, “The Verdict: The Christina Boyer Case,” which explores the American legal system through the story of a Georgia woman convicted in a controversial 1992 murder case, and all of the diverse perspectives within the case. The project inspired a documentary series on Hulu titled “Demons and Saviors.”

Like much of his work, “The Verdict” examines what happens after the cameras leave. It shows those involved, in the aftermath of the case and with their different perspectives, as well as insight into the American criminal justice system.

“I’m not interested in the breaking news moment,” said Banning. “I want to know what happens afterward — how people live with what’s left behind.”

Throughout the event, Banning emphasized that photography can simultaneously be both an artistic and moral act. It isn’t just about what we see, but what we remember. The power of Jan Banning’s work is not only timeless, but crucial to understanding human empathy in a world that lacks it, speaking to all who view it in a unique way.

“His work stands in solidarity with the oppressed, the exploited and the marginalized,” said Carragee. “Through his lens, we are reminded that bearing witness is an act of resistance.”