As vaccine distribution for COVID-19 ramps up across the country, the Suffolk University community discusses their experiences and knowledge of the vaccine.

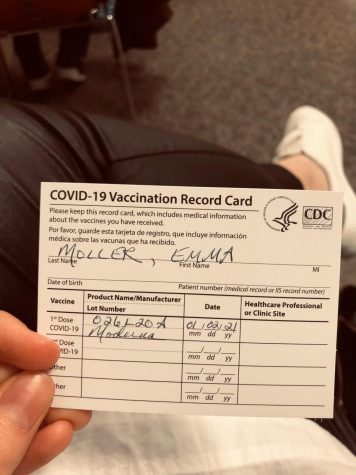

Emma Moller, who graduated from Suffolk University last month with a degree in political science and legal studies, received the Moderna vaccine because she works with patient files in a hospital emergency room.

“I received my first shot on Jan. 2 and second shot on Jan. 28,” said Moller. “The first shot did not hurt, but my arm was a little sore.”

Common side effects of the vaccine include swelling and pain in the arm of injection, fever, chills, fatigue and headache, according to the Center for Disease Control.

“It was emotional, not teary, but moving to think about how we have waited so long for something like this and how our lives have been so different,” said Moller. “You think about all the things you want to do and how your life will go back to normal and it is definitely a happy thing.”

Life can only go back to normal once we have reached herd immunity. Suffolk biology Professor Maghnus O’Seaghdha, explained that vaccinations are the way to reach herd immunity and end the pandemic that faces us.

“Herd immunity is an immunological benefit to a population that comes when a certain percentage of that group are protected from infection,” said O’Seaghdha. “When we are talking about a virus that can cause serious illness or even death, the only acceptable option is through vaccination.”

Yasir Batalvi, a 2020 political science and legal studies graduate from Suffolk, took part in Moderna’s trial studies late last year.

He applied online through the National Institutes of Health website in July, but was not called onto a testing site until Oct. 15.

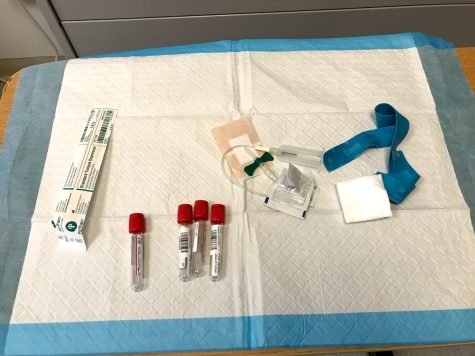

“I went not knowing if I was going to be approved, but after approval, they asked me if I wanted the vaccine and I said ‘sure’,” Batalvi said. “It was a double-blind randomized control style study.”

A double-blind study is when neither the recipient nor the distributor knows if they are receiving the vaccine. In Batalvi’s case, neither he nor Moderna knew if he had actually been vaccinated. This ensures confidentiality in the data being collected about adverse reactions and safety of the vaccine for the general public.

“There is an independent data review board that is collecting all the data coming in,” said Batalvi. “They are the people who send the data to the FDA when Moderna decides they have enough data and are ready to file for EUA.”

The CDC recommends that people who have been vaccinated continue to follow the guidelines outlining social distancing, masks and other protective measures.

“I did not change anything about my daily life from pre-vaccine life because I just didn’t know for a fact if I had received the vaccine, and I did not want to take that risk,” said Batalvi.

On Feb. 3, he was officially released from the study and was notified that he did receive the vaccine.

“I still wear my mask when I leave the house and I limit my social interactions. Not much has changed in my daily life,” said Batalvi. “I am going to remain cautious until we have good quality data and reach herd immunity.”

O’Seaghdha said it would be “a great achievement” if we reach herd immunity by the fall, but that largely depends on the rollout of the vaccine.

In Massachusetts, about 1 million people have received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to vaccine tracking done by the CDC. That places Massachusetts in the top 37% of states and U.S. territories giving out the vaccine.

However, there are still issues surrounding the system to administer the vaccine. Moller explained the one thing she would change about vaccine rollout in Massachusetts is how appointments are being booked. The most common way to book appointments is through an online portal, but she said she does not think that makes getting a vaccine accessible.

“There have been times when people arrive at their appointments, but something wrong happened during their online booking which means a vaccine was never ordered for them and they can’t get vaccinated,” said Moller of her first-hand experience dealing with vaccine patients at her workplace.

On Feb. 5, the Baker administration launched a call center aiming to aid people in booking their appointments. The center can be reached by dialing 211 and, according to NBC Boston, there will be about 500 staffers who speak both English and Spanish.

“The pandemic is hitting minority communities the hardest, and, on top of that, the vaccines are least available to them,” said Batalvi.

In Boston, Black people make up 25.2% of the population, but make up 24% of reported COVID-19 cases and 33% of deaths in the city. Similarly, Hispanics or Latinos make up 19.8% of Boston’s population, but are 31% of reported cases and 12% of deaths.

On Feb. 11, President Joe Biden stood before professionals at the National Institutes of Health and declared that hundreds of millions of Americans would be able to get vaccinated by the end of July.

“Just this afternoon, we signed the final contracts for 100 million more Moderna and 100 million more Pfizer vaccines,” said Biden. “We’re also able to move up the delivery dates with an additional 200 million vaccines to the end of July.”

Right now, there is very little federal oversight of how states decide to distribute the vaccines.

“There are two competing interests,” said Batalvi. “In my personal opinion, we need to balance the incentive of making sure people get closer to the vaccine, but if there are limited vaccines available, and they are sitting in storage, then people should get those vaccines because as people are getting vaccinated, manufacturers are making more.”

O’Seaghdha explained that in the interest of allowing more people to be vaccinated, people who have already gotten the virus may be able to only receive one dose of the vaccine.

“A number of studies demonstrate that individuals appear to have protective responses after one shot if they have also seen the real virus,” said O’Seaghdha. “An amendment like this could speed up vaccine distribution.”