When English Professor Bryan Trabold begins his World Literature class, he asks students for the first words that come to mind when they think of Africa. ‘Safari’ and ‘Giraffe’ are typical answers, though as students who take this class find out, these words don’t really correlate with the continent.

“The combination of little coverage of Africa in [high schools ] and little coverage in the media – means that many people are obtaining their impressions about Africa from American popular culture,” said Trabold. “ And that, to put it mildly, can be problematic.”

The main goal of the class is to broaden students’ outlook on the world and inform them about African cultures and history, as well as women’s issues in the world. This class has been offered since the spring of 2011, and it fulfills students’ social and cultural global perspective requirement.

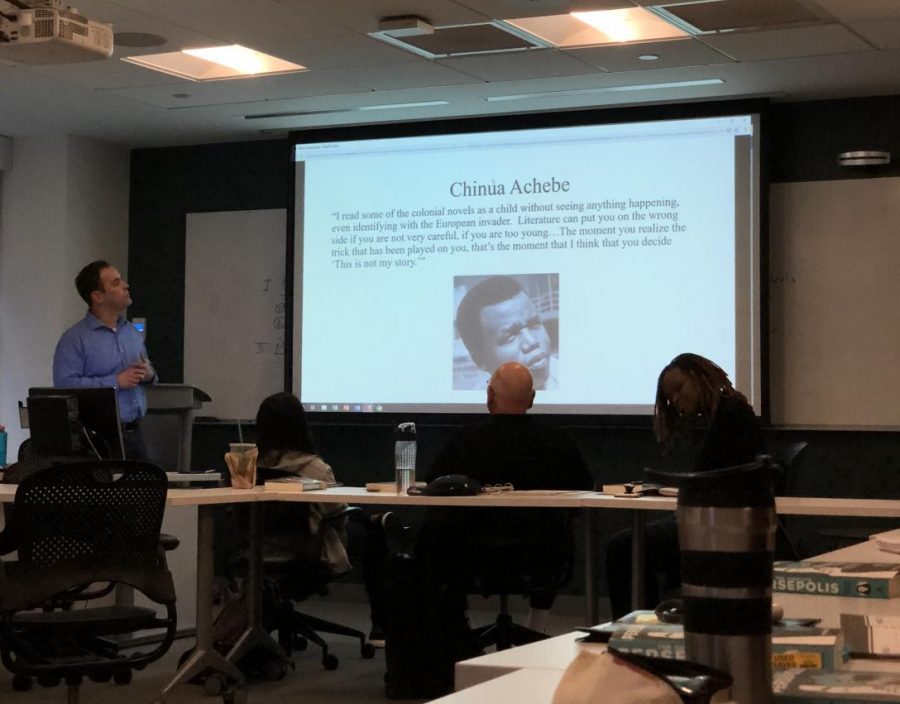

Trabold seeks to bring awareness about Africa to the classroom setting through both film and literature. In his offering of the course, students will read everything from a memoir by Mark Mathabane, who grew up as a black South African under apartheid, to the plays by Athol Fugard, who examines the devastating impact of apartheid. In reading these combinations of text, Trabold said it helps to dispel the myths and false assumptions many people have about Africa and the people who live there.

“The characters in these texts, both real and imaginary, reveal the full humanity and remarkable complexity of people,” said Trabold.

In the class, students learn why the United Nations categorized apartheid as a “crime against humanity.” This system, Trabold said, had a catastrophic impact on millions of people over a period of four decades.

“I’m not exaggerating when I say that I believe every person on the planet should learn about apartheid and the courage of those who resisted it,” said Trabold.

Trabold hopes the class encourages students to take more courses about other cultures, whether the classes are required or not. He has already seen the course help students gain an interest in Africa and the world around them, and bring these lessons back to their own cultures.

One Saudi Arabian student in his class was so inspired by one of the course readings, “Kaffir Boy,” that he wanted to get it translated into Arabic.

Trabold said the student felt the story would resonate with people from his own country. The student reached out to the author and even received a response, as well as contacted people in Saudi Arabia to help translate. Though unsure if the student was successful in getting the book properly translated, Trabold is sure that this is something that made him realize how powerful the book was to the student.

Trabold himself has also spent a significant amount of time studying the continent. He lived there for from 1998 to 1999 with his wife while they were graduate students, and has been back four times since. Though he had been interested in certain African countries, this period of living there is what truly struck him and led him to be as passionate as he is about Africa.

“It’s a remarkable place with remarkable people and a remarkable history.”

One of the most jarring things he said he witnessed while in Africa is the poverty there, and Trabold said there are people who will attempt to immigrate to South Africa, as it is a richer and more developed country than others on the continent. Though there may be parts of South Africa that are deeply poverty-stricken, it’s worse in countries like Zimbabwe.

“There is, of course, poverty in the U.S. but the poverty I’ve observed in South Africa is at another level.”

Trabold said students should remember at the very least that Africa is a continent that consists of 54 different countries―and it is very, very diverse.

“People walk away [from this class] with at least an introduction to some important ideas to consider when thinking about Africa,” Trabold said.