Renaissance painters in the 15th century made history by popularizing the use of oil paints; this century, artists and biologists are making history by learning to paint with bacteria in Petri dishes.

Dr. Mehmet Berkmen, a microbiologist at New England Biolabs and mixed media artist Maria Peñil Cobo spoke at Suffolk University last Tuesday and demonstrated their work using bacteria as a medium of expression. Soon after Peñil moved to Massachusetts in 2010, a chance meeting between her and Berkmen led to nearly a decade of work trying to bridge the gap between art and science.

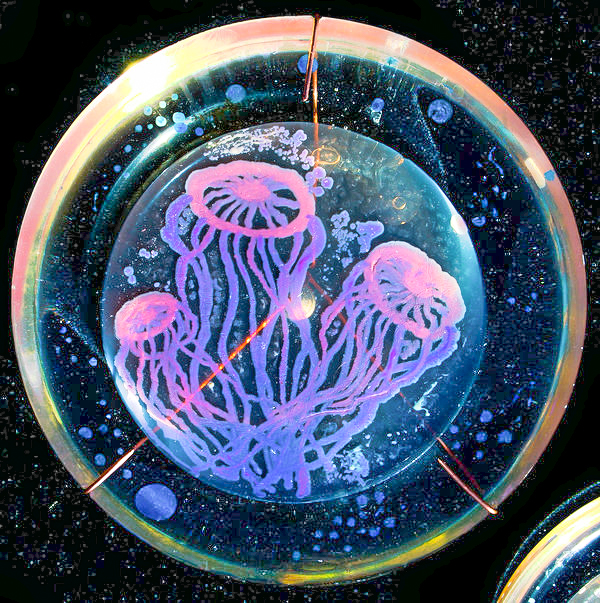

Artist Maria Peñil Cobo “paints” a Petri dish with bacteria

“The best way [for people to see the beauty of bacteria] is to get people to open their third eyes,” said Berkmen in an interview with The Suffolk Journal. “Their brains need to understand how important bacteria are, how present they are, how common they are, how old and diverse they are. In that way, maybe the brain could start respecting them and we could change our perspectives of bacteria.”

For their ‘canvas’ the duo use Petri dishes filled with agar, a jelly-like substance that aids in growing a variety of microbes at different temperatures, and for their living ‘paint’ they use many different species of bacteria that live, breathe and grow over time.

Due to the unpredictable nature of an art medium that can be unpredictable, Peñil does not have full control over the products of her labor.

“When I make a piece, it is not just me doing something to the bacteria, but the bacteria are doing their own thing,” said Peñil. “I think it is amazing that both the bacteria and I are doing something together to make the art.”

Peñil and Berkmen gave nearly 30 Suffolk students a chance to create bacterial art themselves after the lecture, many of whom were science majors. It has been one of their goals for several years to broaden the educational gap between art and science.

Originally from Spain, Peñil explained that although the only science education she ever received was in her high school biology and chemistry classes, her art has always been inspired by nature.

“I was seeing the same shapes in nature as in the human body like with veins and leaves,” she said. “Now from the bacteria, I am getting to know my body inside and out. I work a lot with my fingerprints, with bacteria from my lips, breasts, nose, skin, and it changed the concept of my body for me.”

Dr. Mehmet Berkmen and Artist Maria Peñil Cobo discuss their upcoming bacterial art show in Boston

Peñil’s evolving concept of her own body has been exactly the primary mission of her and Berkmen’s work. They see their craft as an opportunity to “bridge the gap,” between both humans and microbes as well as between arts and sciences.

“I really don’t like the fact that scientists are not trained in art and vice versa,” said Berkmen. “If I had a say I would force every scientist to take art classes, and every artist to take science classes because a separated society is not healthy. There is no good reason for the separation.”

Not only is the art that they create inherently unpredictable, but it also does not last forever. After just six months, the colors of some bacteria will start to fade even after they seal the Petri dishes with epoxy adhesive.

For this reason, part of the process of showing their works to the public has been to take high-resolution pictures when the bacteria are at an ideal point in their growth process.

“As a biologist, you already know that bacteria is good for you, there are good and bad bacteria,” said senior biology major Alicia Cantrell in an interview with The Suffolk Journal. “But thinking about it from a business perspective, it is very hard to get across certain [bacterial] drugs and antibiotics because people don’t see bacteria as a good thing. So this art can really help with that.”

Although it has seen a spike in popularity just in the last decade, scientists and artists have been doing bacterial art

Berkmen and Peñil have won several competitions, including first place in the 2015 Agar Art Contest at the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), and third place in the 2018 ASM contest. They have also attempted to expand into other media, creating an award-winning time-lapse of bacterial art growth, and participating in a TEDx talk.