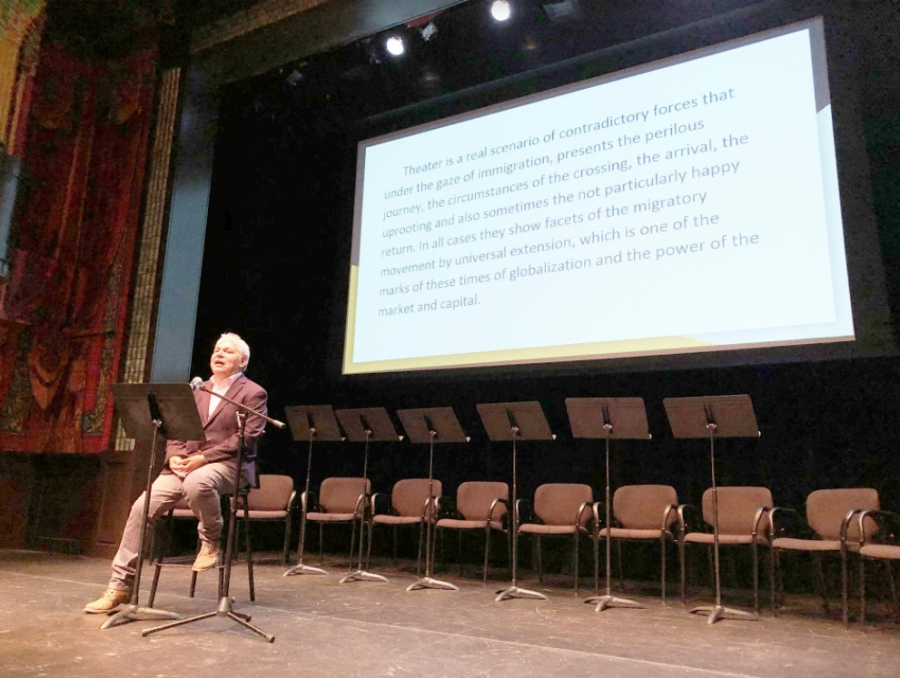

Mexican playwright Hugo Salcedo visited Modern Theatre Tuesday evening for a live condensed reading of his play, “El viaje de los Cantores,” which roughly translates to “The Crossing,” in English.

This artistic presentation vividly portrays the very real crisis happening along the U.S.-Mexican border. Salcedo intended to show the importance of humanizing the atrocities that happen when one attempts to flee their country.

It took Salcedo nearly two years to conceptualize the play so that he was able to fully dive into the true story that needed to be shared with the world. It then took him one month to scrawl his findings across the page, to then have it taken to the stage. In Modern Theatre, Suffolk students, along with outside actors, performed a reading of the play, which was originally written in 1989.

Through his writing, Salcedo depicts the true story of 19 people attempting to cross the border from Mexico into the U.S. and the obstacles they must endure. Salcedo chose to create this play to express his discontent with the situation involving the Mexican people who search for a better life in the U.S.

As an attempt to help others understand the plight Mexican people go through to get to America, Salcedo uses emotional appeal to win the hearts and minds of the audience, regardless of political standing on the issue of border relations.

Salcedo said in an interview with The Suffolk Journal that he hopes that his works in theater will help raise awareness about these issues in a way that is different from conventional news coverage.

Setting the tone for the rest of the production, Chayo, who is about to board the train where all those traveling die, hugs his wife and says goodbye at the beginning of the play in a tearful, emotional embrace. She asks, “when will you return?” Chayo does not reply, and the viewer is left to infer that the answer is never.

Five hours after the bodies were found, the lone survivor of the event, Miguel “el Miqui” Tostado Rodriguez, is talking to presumably an immigration officer. In his trauma, he tells whomever he is speaking to his life story. In an attempt to portray how immigrants are often seen as numbers and forms as opposed to people, Rodriguez’ character goes on a moving tangent about his life when the officer, or whomever he is speaking, is not satisfied with his ability to identify himself.

The exchange is crucial to the emotional appeal of the play, as this man just witnessed many die. He only survived by creating a hole in the side of the train to breathe through while everybody else suffocated.

“I’ve told you everything, sir,” says Rodriguez’ character. “Everyone calls me el Miqui. First at home, by my brothers and sisters and my parents, then in the neighborhood by my buddies.”

Salcedo attempts to convey the message that people are people, regardless of whether or not they are legal. “The Crossing” is a creative representation of how he can contribute to the world in a positive way; by humanizing situations where we stand by and watch.

He goes on to talk about how he likes adventure and narco movies, and how everyone has called him by his nickname since he was a kid. Portraying Rodriguez as a human being, with a past, nickname and interests as opposed to an illegal alien does a justice in helping force the idea that refugees are human beings, not numbers on a spreadsheet.

In the following scene where everybody but Rodriguez perishes, which occurs about five hours earlier to Rodriguez’ plea to the officer, Gavilán Pollero is introduced telling the group of six men to calm down when they are in distress, threatening to not smuggle one man for his lack of money. Pollero is the man that the 19 workers paid to help smuggle them out of the country.

Throughout the reading, there are scenes of camaraderie that arise. The men sing songs in the train while awaiting their fate, trying to help the time pass. Toward the end of the reading, the train comes to a halt, and the men get worried. At 6:15 PM the night of the tragedy, the character of Mosco, Pollero’s assistant, suggests a game where the men all name “cantinas,” or bars and clubs, until they cannot name anymore in order to distract them from the fact the train has stopped. After playing the game for a bit, reality sets in, and they all panic. The men in the train car do not speak again.