By Maggie Randall

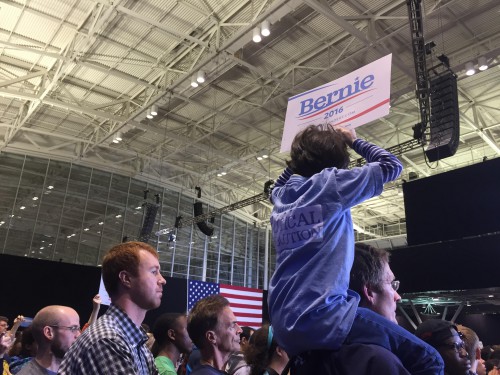

The room was electrified. White and blue signs were waving around in the air. 20,000 people were yearning for a political revolution and 20,000 voices were all shouting one name: Bernie Sanders.

Sanders began in a raspy voice, “My request of you tonight is not to just help me win the Massachusetts primary, but the day after, we win the White House,” he said. The room in the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center erupted.

The 74-year-old senator from Vermont doesn’t look the part of a rockstar, but his popularity has soared since the summer. The packed house was the latest example of that.

In the third quarter, Sanders raised $26 million, closely following democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton, who raised $28 million. The average donation Sanders receives is $30, and 99 percent of his donations are under $100, a fact Sanders proudly mentions in most of his speeches.

More than 200 volunteers, assembled by Andrew Virden, a Bernie Sanders regional campaign manager, were on hand to help control the crowd and enlist support.

Virden had four rules: Don’t run, don’t yell, don’t talk to the press, and don’t talk about any other candidates besides Sanders.

“I don’t even know if there are other candidates besides Sanders,” Virden joked.

Volunteers were divided into teams prior to the rally, including the donation team, which consisted of handing out donation envelopes at the event and inviting supporters to contribute. Volunteers ran the phrase, “Would you like to donate to the campaign?” dry.

Other teams involved crowd control, a sign-in group that recorded attendees’ names and contact information, a media team, merchandise team, Americans with Disabilities Act, and a pep team, which kept the crowd going with chants for the entire three-hour rally.

Virden explained that candidates make the mistake of attacking those running in their party. And that “when Bernie gets the nomination, those other supporters can join us.”

Volunteers included students and Bostonians, all with different reasons for joining the rally that day. College students, young families, elderly couples, and individuals representing seemingly every race came out to advocate.

A sophomore at Emerson College who identified herself as Liz said, “I can’t even vote!” and explained that she is an international student from Singapore. Still, she was drawn to support Sanders’ progressive agenda.

Another volunteer, Paul, who works for a law firm in Boston, explained that he decided to get involved when he realized he was “frustrated with politics and want[ed] to do something about it.”

Sanders expounded on several topics in a speech lasting over an hour. He discussed the need for healthcare reform, voicing his support of Obama’s Affordable Care Act. Sanders mentioned the need for education reform in accordance with prison reform, saying America needs to “invest in jobs and education, not in jails and incarceration.”

After being introduced by Bill McKibben, a leading expert in environmental issues and, particularly, global warming, Sanders later addressed the environment.

“The debate is over. Climate change is real, it is caused by human activity, and it is already causing devastating problems in our country and all over the world,” Sanders said.

Sanders advocated for a tax reform which would support the middle class, and spoke on how unemployment affects women, young people, and people of color differently. He also spoke on the need for gun control, a topic he largely avoids.

As the speech came to a close, Sanders left the room with the sense of a political revolution in how he opposed super political action committees favored by many Republicans, whom he admitted to “disagree with on virtually everything.”

It was not just in the way he vocalized support of progressive economic and social reforms, nor by his challenges towards banks that are “too big to fail,” but in his actions, like having voter registration forms available and pleading everyone to vote.

“When nobody votes, Republicans win. And when large numbers of people come out, we win,” he said.

The room was electrified. White and blue signs were waving around in the air. 20,000 people were yearning for a political revolution and 20,000 voices were all shouting one name: Bernie Sanders.

Sanders began in a raspy voice, “My request of you tonight is not to just help me win the Massachusetts primary, but the day after, we win the White House,” he said. The room in the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center erupted.

The 74-year-old senator from Vermont doesn’t look the part of a rockstar, but his popularity has soared since the summer. The packed house was the latest example of that.

In the third quarter, Sanders raised $26 million, closely following democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton, who raised $28 million. The average donation Sanders receives is $30, and 99 percent of his donations are under $100, a fact Sanders proudly mentions in most of his speeches.

More than 200 volunteers, assembled by Andrew Virden, a Bernie Sanders regional campaign manager, were on hand to help control the crowd and enlist support.

Virden had four rules: Don’t run, don’t yell, don’t talk to the press, and don’t talk about any other candidates besides Sanders.

“I don’t even know if there are other candidates besides Sanders,” Virden joked.

Volunteers were divided into teams prior to the rally, including the donation team, which consisted of handing out donation envelopes at the event and inviting supporters to contribute. Volunteers ran the phrase, “Would you like to donate to the campaign?” dry.

Other teams involved crowd control, a sign-in group that recorded attendees’ names and contact information, a media team, merchandise team, Americans with Disabilities Act, and a pep team, which kept the crowd going with chants for the entire three-hour rally.

Virden explained that candidates make the mistake of attacking those running in their party. And that “when Bernie gets the nomination, those other supporters can join us.”

Volunteers included students and Bostonians, all with different reasons for joining the rally that day. College students, young families, elderly couples, and individuals representing seemingly every race came out to advocate.

A sophomore at Emerson College who identified herself as Liz said, “I can’t even vote!” and explained that she is an international student from Singapore. Still, she was drawn to support Sanders’ progressive agenda.

Another volunteer, Paul, who works for a law firm in Boston, explained that he decided to get involved when he realized he was “frustrated with politics and want[ed] to do something about it.”

Sanders expounded on several topics in a speech lasting over an hour. He discussed the need for healthcare reform, voicing his support of Obama’s Affordable Care Act. Sanders mentioned the need for education reform in accordance with prison reform, saying America needs to “invest in jobs and education, not in jails and incarceration.”

After being introduced by Bill McKibben, a leading expert in environmental issues and, particularly, global warming, Sanders later addressed the environment.

“The debate is over. Climate change is real, it is caused by human activity, and it is already causing devastating problems in our country and all over the world,” Sanders said.

Sanders advocated for a tax reform which would support the middle class, and spoke on how unemployment affects women, young people, and people of color differently. He also spoke on the need for gun control, a topic he largely avoids.

As the speech came to a close, Sanders left the room with the sense of a political revolution in how he opposed super political action committees favored by many Republicans, whom he admitted to “disagree with on virtually everything.”

It was not just in the way he vocalized support of progressive economic and social reforms, nor by his challenges towards banks that are “too big to fail,” but in his actions, like having voter registration forms available and pleading everyone to vote.

“When nobody votes, Republicans win. And when large numbers of people come out, we win,” he said.