Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) presents an imaginative display of color and form in its new exhibition, “Figuring Color.”

The exhibit, organized by ICA Senior Curator Jenelle Porter, features the works of four artists: Kathy Butterly, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Roy McMakin, and Sue Williams.

Separately, the various paintings, installations and sculptures hold the agendas of their creators, but in unity they serve to educate about the use of color and form in representing notions of the body, both physical and mental.

Ironically, a literal representation of the body never appears in the exhibition.

“Each work in ‘Figuring Color’ uses color to represent a metaphorical body — a body rendered as vessel, pure color, abstraction, line, field, or allegor,”’ Porter said in a press release. “At the beginning of the exhibition, color is used to evoke a physical representation of the body that becomes increasingly emotional as you move through the galleries.”

Each of the four “Figuring Color” galleries communicates a new theme particular to the experience of color, form and the body.

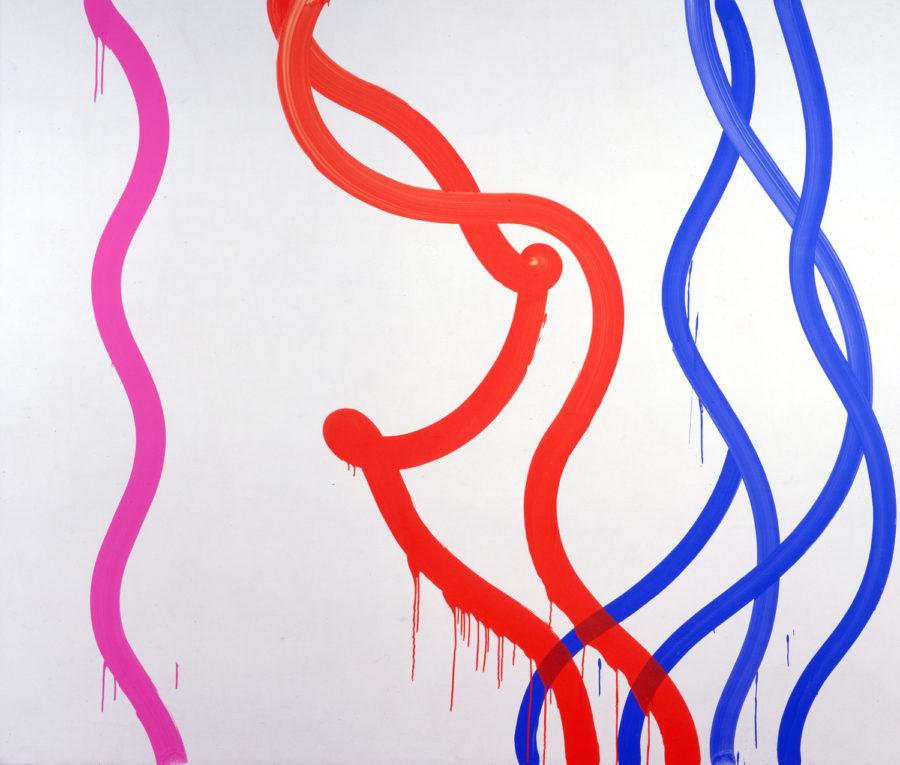

The first gallery serves mainly to emulate the physical and exterior aspects of the body. Warm, fleshy colors blend coolly with the provocative forms of the art.

Butterly’s small, glazed ceramic sculptures, whose promiscuous form and blend of fleshy and bright colors are intended to provoke, humor, and shock the viewer; certainly possess their own personality.

A striking work by McMakin also resides in this gallery. A flesh-colored chair with a rounded bottom reminiscent of a human behind, it serves both to remind of the body (it is an object directly in contact with the body) and imitate it through its color and shape.

The connecting gallery employs the themes of the unseen: the interior, abstract, and absent. The viewer enters through a red, beaded curtain by Gonzalez-Torres named “Untitled (Blood).”

The work, created in 1992, calls attention to the AIDS epidemic, from which Gonzalez-Torres passed away.

Also in this gallery are Williams’ paintings, which use the interior body to relay political messages about topics like violence and capitalism.

Depicted in her work “American Enterprise” (2009) are human organs in the patriotic colors of red, white and blue, a response to the US involvement in war.

The other two spaces in this gallery are remarkably different from each other. One copes with memory and sadness, surrounded by many blues and grays; the other is jubilant and eye-popping in nature. It seems, only at first, this oddity diminishes the impact of the exhibition, but it does well to portray a rounded example of the effect color and form can have in art.

Displayed in the third gallery is Gonzalez-Torres’s 1991 sculpture, “Untitled (Lover Boys),” a self portrait of the artist and his partner, who also lost his life to AIDS. The sculpture is meant to weigh 355 pounds, about the weight of the couple combined.

Used as material for the portrait is blue and white wrapped candy that lies on the floor of the gallery, intending a feeling of melancholy. The viewer is meant to take a piece of the candy and consume it, an effort of the artist to share a part of himself with his audience.

McMakin also uses color to explore memory and loss in his work. Named after his mother, “Lequita Faye Melvin” (2003) consists of individual sculptures created from the sketches he made from memory of the furniture found in the homes of his family. Each sculpture lacks the original color of the furniture and is instead painted a somber grey.

Seen in the final gallery space are the lively works by each of the four artists, together for the first time in the exhibition. A small but significant encore appears near the exit, “Untitled (Fear),” Gonzalez-Torres’ blue-tinted mirror, inviting visitors to view their own reflection.

“Figuring Color” will exhibit until May 20, 2012.