The first time Suffolk University senior and Team USA skater Ryan Dunk stepped on the ice at 8 years old in a public skating session, a woman asked his mother what level he was competing at and who his coach was.

“I was trying to copy the figure skaters in the middle doing spins… my mom told the woman that it was just my first day,” said Dunk.

Dunk’s career began to take off from there, beginning with group lessons for a year followed by private lessons, a huge step in the world of figure skating; in addition to joining a skating club .

During the first year he began to skate, Dunk was told by his parents that they didn’t want to buy him a pair of figure skates because they didn’t believe he would stick with the sport and that it was just a phase. He would continue on to travel across the world to Armenia, China, Austria, Poland and The Netherlands.

“I always was the kid that was very independent and would teach myself things,” said Dunk. “I would go home and watch Youtube videos of skaters and try to replicate moves at the rink; I’m a visual learner.”

By 9 or 10 years old, Dunk told his parents that figure skating was what he wanted to focus on.

Dunk attended his first nationals at the juvenile level when he was 13 years old in Boston, where he would later go to college. The national competition in figure skating is a showcase at five levels of competition: junior, intermediate, novice, junior and senior (the ranking that Olympians compete at).

Dunk explained how one of his proudest achievements has been competing at nationals every year since he was 13 years old. This includes 2015 at the intermediate level, 2016 at the novice level, 2017-2019 at the junior level, and finally at the senior level since 2020.

Dunk won the national competition at the junior level in 2019. After competing in his first international competition, he realized that Baltimore could only offer him so much, and decided to make the move to Boston and finished his senior year of high school online.

“That year was a really big transition year,” said Dunk. “To win nationals… it showed all my hard work had paid off.”

Now in Boston, Dunk lives with a host family while he trains at the Boston Skating Club. After winning nationals in January of 2019, Dunk enrolled at Suffolk in the fall as a part-time student because he had three international competitions in the fall, the qualifying season for nationals.

At the time, Dunk’s coaches wanted him to take a gap year, but Dunk knew he needed balance in his life.

“School is a distraction from skating and skating is a distraction from school in some ways,” said Dunk. “I think it’s good to have something you enjoy that’s individualized to channel your passion outside of school.”

Dunk would practice five days a week as a student. Being a college student, Dunk has to manage his time between the ice and hitting the books, so his skating regimen may look different compared to most.

“I would normally skate for two hours five days a week. Three days a week I’d be doing workouts at the gym with a trainer,” said Dunk. “Before I moved to Boston and started college, I’d be there all day.”

For Dunk, the COVID-19 pandemic was a blessing in disguise to help him come to terms with how the toxic culture in skating was affecting him and his body.

In December 2019 while preparing for his first senior national competition, Dunk’s ankles had swollen due to bursitis from over-training. Since he was training so much, Dunk explained that his boot would wear down, not providing enough support during jumps and tricks.

Bursitis is not uncommon for figure skaters, and the bursa can usually be drained. However, due to so much scar tissue building up, Dunk was not so lucky. Once the season ended for him in January, Dunk underwent two procedures and the doctor found bone bruises.

Dunk explained that because he was not skating as much, the coaches he had at the time put an emphasis on controlling his eating and exercising.

“I was getting skinnier and I was getting praised by people. If anything, [people were] actually encouraging me.” Dunk said.

Outside thoughts of gaining weight and losing his stamina began to infiltrate Dunk’s own thoughts and he began limiting his eating,

“There’s this belief that you have to be like a waif in order to rotate… but you need strength and stamina and food to keep going,” said Dunk.

Eating disorders are prevalent in aesthetic sports, such as figure skating. According to the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Jenny Kirk, a former competitive skater, estimated that 85% of figure skaters struggle with some type of eating disorder.

In the 2018 Olympic Winter Games, two figure skaters had to sit out of the competition due to eating disorders.

“Athletes are at 2 to 3 times increased risk for developing an eating disorder compared to nonathletes,” said Paula A. Quatromoni, DSc, RD, the chair of health sciences at Boston University, according to Walden Eating Disorders.

“There’s been a lot of misinformation. I’ve had coaches who didn’t want me to do strength training because it would make me ‘bulky’, said Dunk. “I’ve had coaches tell me to not drink that much water. All sorts of things that aren’t scientifically accurate.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, “roughly 33% of male athletes in weight class sports (wrestling, rowing) or aesthetic sports (bodybuilding, gymnastics, swimming) are affected by eating disorders.”

“It’s definitely an open secret that it feels like no one wants to address,” said Dunk.

Dunk has been a staunch advocate for more transparency around eating disorders, speaking out about figure skating’s toxic culture of body shaming and weight loss. He is part of STRIPED, the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorder, as well as a research intern in the eating disorder program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

He also has pushed for MA to pass An Act protecting children from harmful diet pills and muscle-building supplements (S.1525/H.4271), bills introduced by Rep. Kay Khan and Sen. Michael Rush.

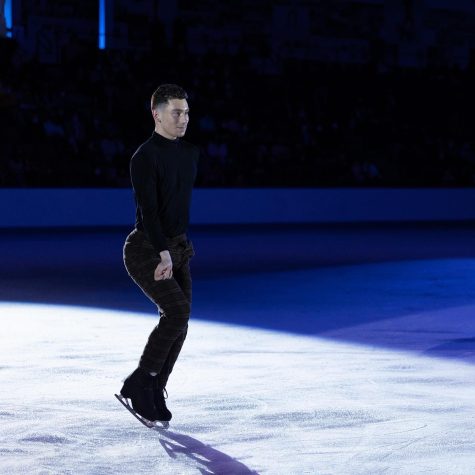

The Team USA figure skater competed in his last competition at the senior nationals in Nashville, TN this past January. He rounded out his career competing against notable figure skaters such as Olympian Nathan Chen with a score of 191.36 (65.66 short program and 125.70 free skate).

What’s next for Dunk? He said it’s time for the next chapter in his life as he graduates from Suffolk, but skating is something he’ll always keep with him.

“This summer when I start working a full-time job, I’ll still try to [skate] on the weekends,” said Dunk. “It was my life since I was 8. Now it’ll have to be more of a hobby, but it’ll still be a major part of my life forever.”

Dunk has begun to shift into choreography and coaching — a side of the sport he’s always enjoyed.

“So much of skating is focused on jumps and competing. Now that I’m doing choreography and shows, it’s artistic and creative,” said Dunk.

For those who are interested in seeing Dunk perform, he will be a part of “An Evening with Champions” at Harvard University on April 9 and 10. The event is a charity non-profit committee dedicated to fighting cancer by raising money for The Jimmy Fund. Tickets are available for students online for $15.

Follow Katelyn on Twitter @katelyn_norwood

Judy T. • Apr 6, 2022 at 12:40 pm

Thanks for this article about Ryan Dunk. I’ve enjoyed following his skating career. The first level mentioned should be “juvenile” where it says “junior” twice in the sentence. Also, when he won nationals in 2019 it was at the junior level. Nathan Chen is the Olympic champion (gold medalist in the individual men’s event), btw, not just an Olympian. I appreciate your coverage of figure skating and wish Ryan the best of luck!