Six panelists came together to discuss racism, public health, contemporary art and how they can be tied together at an Oct. 29 event hosted by the Institute of Contemporary Art.

The Institute, better known as the ICA, hosted this live-feed panel to emphasize two public health crises. The first is the well-known and discussed COVID-19 virus that is affecting people on a global level.

The second is a less talked about but just as dire pandemic: racism. Racism has been declared a public health crisis by 25 out of 50 states, opening up a discussion that is beyond necessary. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh also declared racism a public health crisis in Massachusetts back in June.

The moderator of the panel, Jeneé Osterheldt, is a culture columnist at The Boston Globe. Osterheldt’s work often focuses around Black lives and people of color.

Dr. Kimberlyn Leary, a panelist at the event, explained a public health crisis as a “concurrent overlapping crises, the problem is one that the forces accelerate and lay over one another.”

Leary, an associate professor at Harvard, introduced the subjects the panel would discuss, including COVID-19, racism as a public health crisis, George Floyd and how each of these topics affects the mental health of the Black community.

“Each protective action we take brings new stressors, uncontrollable things are happening, there’s a lot of ambiguity, you have to adapt. Racism is a specific stressor,” Leary said.

She said that as millions of Americans sit at home during the pandemic, they have opened themselves up to the reality of racism.

“More Americans are willing to see themselves in a different light and racism isn’t something that is in other neighborhoods,” Leary said. “It is in their neighborhood, it is in my neighborhood.” .

The next panelist, Dr. Karilyn Crockett brought the discussion closer to home. As Boston’s chief of equity , she has the unique position of incurring change. The Department of Equity is a fairly new addition to Boston, and one that was spurred by the call for action.

“There’s so much wisdom and insight to be gained from what it means to call a thing a thing. In the act of calling out racism as a threat, as a toxin, as something that we must root out, we have an opportunity to really reset the nature of our society,” Crockett said.

Crockett later gave one of the most impactful lines of the night.

“Who gets to name things and define what things mean? We all have the space and the power to define and call out what our reality is. The problem that we are living through is the idea of who gets to solve,” Crockett said. “Who gets to name and think has become so narrow and a manifestation of white supremacy and other systems that say there’s some kind of hierarchy? There’s a toxic order to saying no, not you, you can’t hurt, you can’t solve, you can’t heal.”

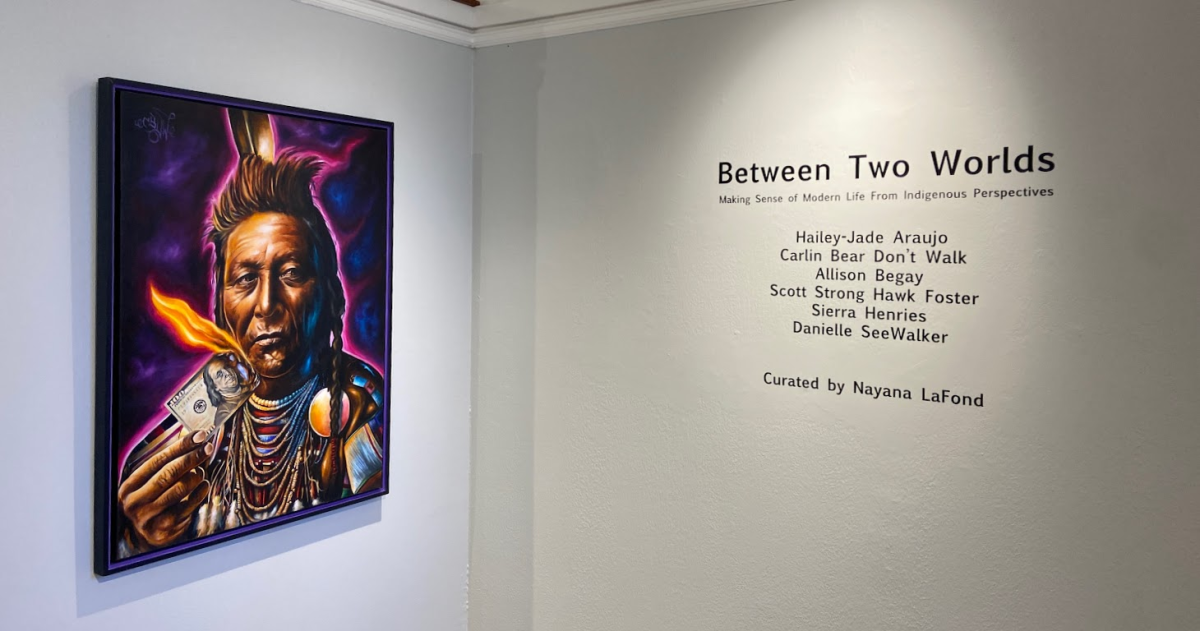

The first two panelists set the groundwork for the rest of the conversation. As the panel turned to the artists, a different side of the same argument was illustrated. The conversation changed significantly from the words of medical professionals and government employees to that of artists. However, the underlying theme and messages remained steadfast.

As Osterheldt introduced the two artists, OJ Slaughter and Bill T. Jones, the connections between racism, public health and contemporary art were drawn.

These two artists use different mediums. Slaughter is a visual artist, utilizing photographs and documentaries, while Jones is a choreographer, using his own body and the bodies of others to make art.

Slaughter has recently been on the ground covering protests and giving a voice to the people.

“My role as an artist right now is to make sure that other voices feel like they have the space to speak,” Slaughter told Osterheldt. “Even if I disappear, the work will live long enough so that people can come through, see these images and the images will speak for themselves but they’ll also be able to see themselves in the images.”

Slaughter worries that they are putting their own misery out for others’ joy and their entertainment, but also knows how strongly their work is needed.

“The idea is that I’m telling the history of right now through Black voices, for Black voices and eliminating the white gaze through this work,” they said.

“I think a lot of people see these past protests, these past riots, we’re not actually seeing the joy and the power that is behind these protests, and the organizing and community that really comes together to make all these things happen,” Slaughter answered in response to being asked about their work.

When Jones chimed in, it was to provide stories that revolved around his love life, his youth and how he has grown, loved and lost. But he always came back to art and to his passion as an artist.

“An artist is a person and that person has a location in the society, gender, male, female, trans, that person has a bank account, that person has a class. Now what should an artist do? What does that artist need to do? That’s it for me right there,” Jones said. “Artists should be troublesome.”

Slaughter and Jones so neatly tied together the worries and hopes of Dr. Leary and Dr. Crockett, even offering them a sense of balance.

They discussed how art is so deeply important and impactful to the lives of Black Americans, in particular, how it helps those who are struggling. The art they provide is beneficial to the mental health of those they touch, they said.

The last panelist, Amanda Taffy, a Doctor of Public Health student at Harvard, spoke about the moments in time, and concluded the panel in a way that left the audience members with something to truly consider.

“This moment, it’ll be gone in the next moment,” Taffy said. “But it is also the moment that in many ways will define for some time a great many people.”