Conversations around “anti-racism” have helped provide a clear way for individuals to fight racism, reflect upon their own biases and create real change within each other, as discussed at the Museum of Science recently.

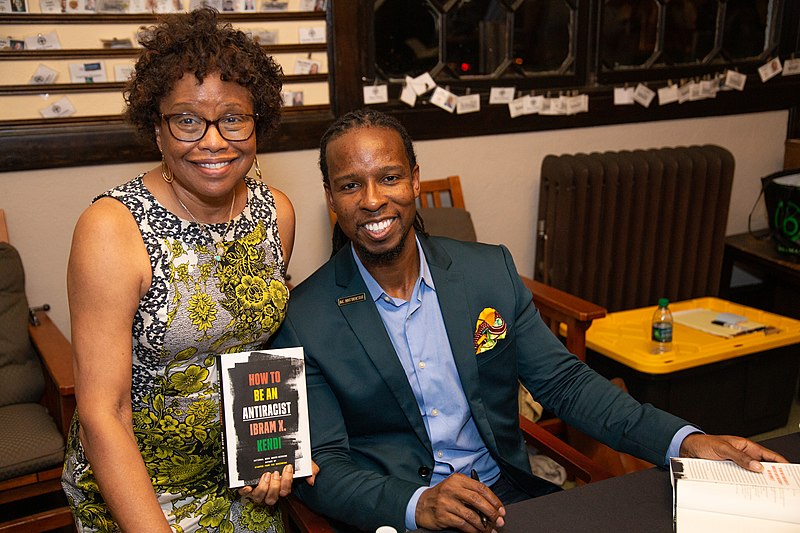

On Oct. 14, the museum hosted a live virtual discussion between Dr. Ibram Kendi, author of the #1 New York Times Bestseller, “How to be an Antiracist,” and Boston Artist-in-Residence and local activist L’Merchie Fraizer, about the current issues of equity and racial justice in the United States.

Kendi told the audience that the idea of anti-racism was inspired by the research he gathered while writing his book, “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.” He dove deep into the history of racist ideas, right down to their origins, in which people simply claimed their racist ideas were “not racist.”

He realized he needed a new word to define ideas that are the opposite of racist. Thus, the word “anti-racist,” meaning the opposite of racist, was sparked. While racist ideas enforce harmful stereotypes and a system of racial oppression based off of these stereotypes, anti-racist ideas say that “power and policy, and practices and conditions,” are also the problem, said Kendi.

In a PowerPoint presentation, Frazier gave a glimpse into the history of racist ideas. She claimed the view of humans as property, dating back to the enslavement era, is responsible for the creation of these ideas.

“I think this idea of white supremacy and its relationship to what you are talking about in terms of racist ideology, is the idea of white possessive logic,” said Frazier.

Throughout history, the oppressed have been blamed for their own oppression, said Kendi. But as the speakers discussed, these communities need to recognize that the reason for their oppression is actually racist policies, systems and culture.

“So that’s why we need to dismantle racism, first and foremost, so people of color could have a chance at belonging in this country,” said Kendi.

Frazier’s work as the director of education at the Museum of African American History and resident artist at Northeastern University, has been inspired by the beauty standards that have been set globally. Specifically, her art focuses on how Black women see themselves as a result of how others see them.

“The aesthetics and beauty in art, and the challenges of Africa being read as ugly– it’s the terror and the association of Europe with the sublime in how the standards of beauty have been affected by that and how we sit in that seat,” said Frazier.

On the topic of beauty standards, Kendi explained that there is beauty in the “human rainbow;” beauty is in the diversity of the human race. The professor said beauty is subjective, and in order to change the standard of beauty to what it should be, humans need to reevaluate its terms or dispose of it altogether.

“We can really embrace the entirety of that spectrum [of color] while not imagining that the darker or the lighter side of the spectrum is more beautiful or more ugly– it’s just more different,” said Kendi. “And I think at some point we need to have a sort of a beauty standard that actually is reflective of human difference.”

Both speakers told the audience that they have recognized that there is racism and inequities present between “light and dark-skinned” individuals, and that this colorism greatly affects how Black people see themselves.

Kendi explained the history behind these inequities, in which mothers were “enslaved and likely raped” by white slave owners. Therefore, during the enslavement era, the lighter a person was, the more beautiful, or acceptable, they were deemed to be in the eyes of society. He said this view of skin color is still an issue today.

“It’s not nearly enough to eliminate the disparities between Black people and white people, particularly as it relates to color,” said Kendi. “We must also eliminate these disparities between darker people, whether they speak Spanish or English or French and lighter people who may identify as Latinx or Black or Asian, because that is another form of racism.”

He said people need to recognize when there is not enough diversity in their life and educate themselves on all different people and identities.

“One of the things that I’ve made a mission for myself is to just learn so much about everything I don’t know and every group of people that I don’t know, because the more I understand different groups of people that come from different walks of life, the more I actually even understand myself,” said Kendi.

He encouraged people to recognize that “the beauty of humanity itself is all of the cultural and ethnic and even color sort of diversity.”

Kendi encouraged society to stop looking at Black neighborhoods as “violent Black neighborhoods,” and instead look at them as “violent unemployed neighborhoods.”

“So many Americans have been taught there are neighborhoods that are more violent and dangerous, and the reason why they are violent and dangerous is because that’s where Black people live. So they’ve been taught that Black people are dangerous and violent and they make neighborhoods dangerous and violent,” said Kendi.

He went on to share that the commonality between violent and dangerous neighborhoods are higher levels of long-term poverty and unemployment, not race. He proposed that by identifying unemployment as the problem, it provides a new solution for the crime.

Kendi said these communities do not need more police presence and that their members do not need to be separated from society through incarceration. Instead, they need jobs, resources and opportunities.

“I think we need to be thinking about building our politics that ensures every sort of community, no matter their racial makeup, has opportunities and resources so we stop demonizing those communities and the people in them,” said Kendi.