William Darity, Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy at Duke University, spoke on the case for Black reparations and its feasibility at the Boston University (BU) School of Public Health on Nov. 6.

The case for Black reparations is not a new- found idea, especially within the Black community. However, the issue has been at the forefront of today’s political climate and it is a divisive one. Most recently the public saw the issue brought up during a Democratic debate when candidate Marianne Williamson called slavery, “a debt that is owed.” Darity himself has been asked to testify in front of Congress about his research on the issue.

While the connection between reparations and public health sciences may not be prominent, the connection is one that was examined by inviting Darity to speak.

“Reparations is a complex and controversial

topic in the public conversation and that is exactly why we are discussing it. It’s important to public health to find the tough solutions to challenges that are important to the health of the public, “ said Sandro Galea, the dean of the School of Public Health.

The (BU) School of Public Health’s Activist Lab wants to educate and innovate, and the topic of Black reparations coincides with their goal of creating change in public health.

“Racism drives health inequalities and reparations [would be] a tremendous help,” said Candice Velanoff, a professor of public health at BU.

Darity in his research on reparations, spoke of three parts reparations contain: acknowledgment, redress and closure (ARC). To have acknowledgment, it must consist of a form of an apology and a recognition that a party has benefited from the other, such as the United States, benefiting from Black labor. Redress would have the form of restitution, one that Darity believes

must be in the form of individual payments to the parties affected. Closure in this scenario would be a sort of understanding between the victims and the culpable party that the debt has been paid.

For Darity, his two main arguments for reparations was to close the racial wealth gap, and to retain the memory of those who have been oppressed.

Darity explained that reparations aren’t a newfound concept and historical precedents support his case. Governments have paid reparations to victims of atrocities; the Germans to holocaust victims, the U.S. to Japanese-Americans during World War II and families of victims during 9/11.

“I believe reparations are possible. [The United States] gave them to Japanese-Americans who were unfairly incarcerated during WWII,” said Kendal Zonghi, an undergraduate law major at Suffolk. These reparations were the $3.3 billion in today’s dollars to Japanese Americans in 1988 for the internment of more than 100,00 Japanese from 1942 to 1945. Germany paid the equivalent of $7 billion to Israel and $1 billion to the World Jewish Congress. The country also dis- mantled companies that used Nazi-slave labor and judged war criminals at the Nuremberg Trials.

“This is not something that is a fantasy,” said Darity.

During the talk, Darity mentioned how the idea of reparations is not about

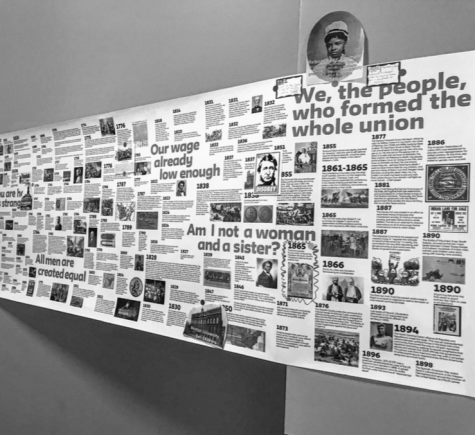

A display at the Black reparations event at Boston University School of Public Health

individual or personal guilt. Instead, it is about national responsibility and recognizing the U.S. government as the copable party. The government as a source of law and authority led to the legal conditions to support slavery and Jim Crow.

“It is a misnomer to refer to ‘slavery’ reparations,” said Darity. ”Slavery is certainly an important dimension for the case for reparations.

Slavery is the crucible that created America’s version of white supremacy. But it is not the only reason for reparations.”

Darity’s argument is that while the proposed reparations include slavery as a central part of the argument, it is not the only part. Included as well is Jim Crow (state and local laws passed to enforce segregation), legalized segregation and the post-civil rights era.

Furthering Darity’s point, the effects from slavery are both cummulative and intergenerational. This means that relatives of slaves have carried a burden of oppression and injustice ever since their ancestors were denied 40 acre of land a mule, according to what was supposed to be given after the end of the Civil War.

“The deprivation of the 40 acres was essentially a consolidation of the failure to provide the formerly enslaved with full citizenship, the citizenship claim that is being made by Black descendants of American slaves is one that can only be fulfilled adequately with the adoption of a reparation,” said Darity.

In America, the national population and the national wealth are not linear. 13-14% of the population is Black, yet they only hold 3% of the nation’s wealth. Reparations is a key aspect to addressing the racial wealth gap according to Darity.

“Hearing that Black Americans make up 13% of the population but only have 3% of the wealth, so naturally they should have 13% of the wealth- it made sense and put a really simple logic on why reparations are necessary,” said Zonghi.

Currently, a bill sits in the House for consideration. Entitled H.R. 40, the bill would allocate funds to form a commission to “Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act” according to Congress. While Darity does not believe the bill is satisfactory in its current form, the situation is more optimistic for passage since hearings were held in June.

“America’s failure to provide full citizenship for Black Americans is a failure to constitute this nation as a true democracy,” said Darity. “And in so far as that is the case, Black reparations are also a prerequisite for making America great for the first time.”