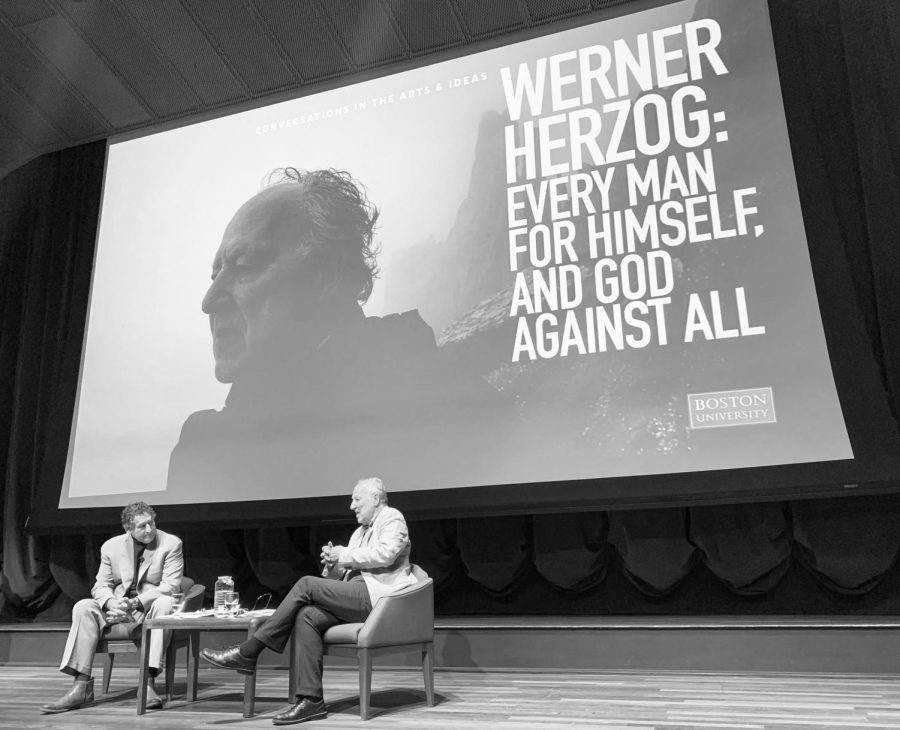

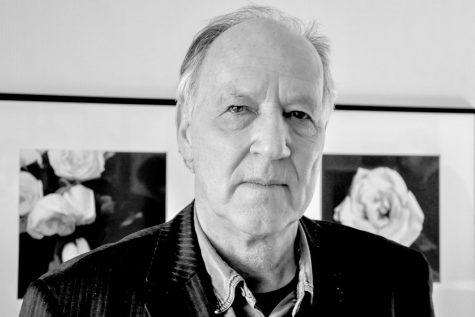

Acclaimed German director Werner Herzog visited Boston University (BU) on March 25 to discuss his career in filmmaking as part of the university’s ongoing “Conversations in the Arts and Ideas” series. Herzog’s lecture, “Every Man For Himself, and God Against All,” not only outlined his career highlights, it illustrated the insight Herzog’s films have given audiences for decades.

“No matter how big the dream or impossible the quest, at the very foot of the heart of his films is humanity’s relentless struggle to find meaning, despite the indifference and hostility of the universe,” said BU classical studies professor Herbert Golder, a longtime colleague and friend of Herzog who interviewed him throughout the evening.

Born in 1942, Herzog was raised in a poor, remote mountain village in Germany that had no access to running water, TV or telephones. His family starved for several years when he was young, and he had no exposure to film until he was 10 years old.

After stealing a camera from a film school and using it to make his first movie at age 19, Herzog has been recognized by Time Magazine as one of the world’s top 100 influential people and he has created more than 50 films over the course of his half-century long career. Each of his films, including “Grizzly Man,” “Fitzcarraldo” and “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” captures the human condition and spirit while offering audiences something they’ve never seen before.

“What initially drew me, a classicist, to Werner’s work was the uncompromising starkness of his vision,” said Golder, who has made 10 films with Herzog.

Many of Herzog’s films are well-known for featuring awe-inspiring landscapes that present the beauty and indifference of nature. Herzog explained to the audience the danger he faced while filming a hazardous volcano that was about to erupt for his 2016 Netflix documentary “Into The Inferno,” before reading an excerpt from the film that shows how enticing nature can still be even in such perilous states.

“It is hard to take your eyes off the fire that burns deep under our feet, everywhere, under the crust of the continents and sea beds. It is a fire that wants to burst forth, and it could not care less about what we are doing up here,” said Herzog on stage. “This boiling mass is just monumentally indifferent to scurrying roaches, retarded reptiles and vapid humans alike.”

Herzog said filmmakers must be patient with landscapes in order to capture their essence; that they must be able to read them rather than manipulate them. He attributes his lesson to his grandfather, Rudolf Herzog, who discovered the 1000-year-old Temple of Asclepion on the island of Kos in Greece, despite people’s doubts and despite not being an archeologist.

Music is also an essential tool in Herzog’s storytelling as it creates the mood and sets the scene. For example, the end of his 2005 science fiction film “Wild Blue Yonder” concludes with montages of landscapes as impassioned music plays in the background. The director compared choosing a film soundtrack to his experience of staging operas because the meanings of films and operas can both be altered through song selection.

“Transformations, they come sometimes through music. All of a sudden, you will see something that you’ve never seen before in the landscape,” said Herzog.

Although his movies depict the sublime, the director made it clear that he does not intend for his films to seem romantic. Herzog added that his films are not always meant to have a deeper meaning, and he told the audience about a scholar who once asked him to describe what the complicated implications were of one of his films.

“A dancing chicken is just a dancing chicken,” said Herzog to the scholar, explaining that sometimes things are as simple as they appear.

Herzog also said that he does not re-watch his films. If he does, he feels like he is seeing another person’s work since he has grown so much since making them.

“I don’t want to have introspection,” said Herzog. “We should not illuminate every darkness in our soul because humans would become uninhabitable if we did.”

Golder said that Herzog has an eye for making something out of nothing because he captures things as they are without using CGI or special effects.

However, Herzog is open to experimentation. His film “Heart of Glass” was shot with all of the actors so deeply under hypnosis that they would often open their eyes without waking up.

In addition to the actors being hypnotized while filming, Herzog showed the movie to a hypnotized audience of about 300 people and observed some of their strange reactions. Some people described feeling like they were in what is now known as virtual reality and the elderly often struggled to wake up. However, not everyone was susceptible to the hypnosis, especially young children with short attention spans.

Herzog said his visions for films are never planned, but rather ideas that “come at [him] like burglars in the night.”

He told aspiring filmmakers in the crowd to always strive for originality, bend the rules a bit if need be and to follow their passions.

“Step beyond what is the usual on the set,” said Herzog. “Never do any harm to anyone but use, if necessary, a healthy amount of creative energy. That’s why I’d teach you how to pick a safety lock, that’s why I’d teach you to forge a shooting permit in a country that has a military dictatorship.”

Above all else, Herzog said filmmakers must always have courage.

“Just have the courage through your own culture, through your own upbringing, through your own vision and then you’ll define [your career],” said Herzog.