In January 1990, Boston Globe photojournalist Mike Carroll received a phone call that landed him on the next flight to Romania – a call that would end up changing his life forever.

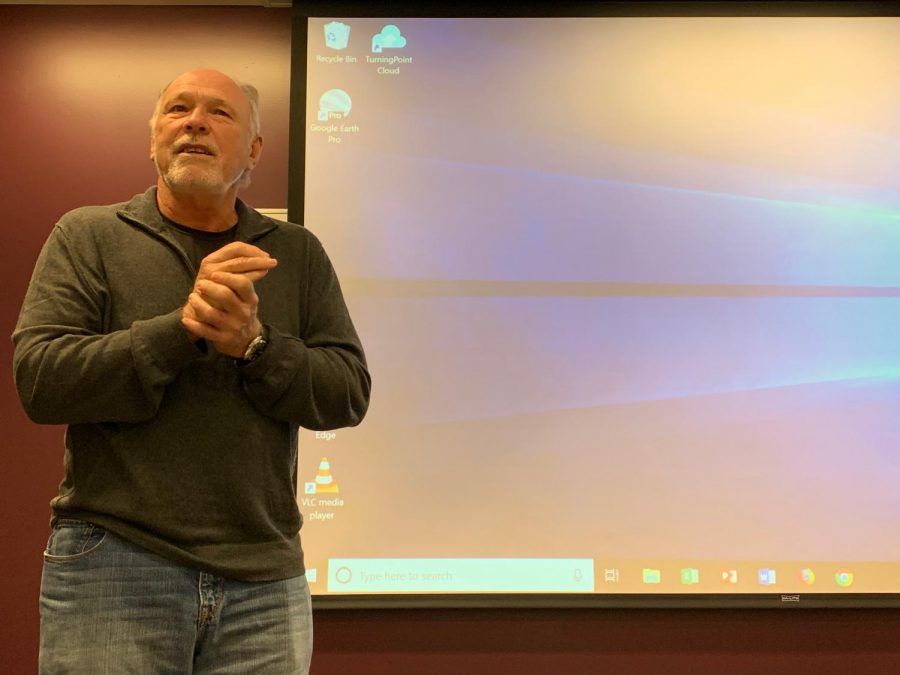

Last Wednesday in the Somerset Building, hosted by the Romanian Children’s Relief (RCR), Suffolk University held a screening of the documentary Hand Held, a film directed and produced by Don Hahn featuring Carroll’s journey as a reporter in Romania and the hardships of the children in the nation after the fall of the communist regime in 1989. The event was followed by a question and answer session with the photojournalist.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it symbolized the first steps towards the end of communism throughout Eastern Europe. This sparked the beginning of the Romanian Revolution. Romanian citizens lashed out with protests against dictator Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist regime.

Ceausescu fled the nation on a helicopter with his wife until they were captured by the anti-Ceausescu military and executed on Dec. 25, 1989. Carroll arrived to Romania after the death of Ceausescu and the fall of the regime.

There was a power outage when the reporters arrived. Carroll explained that as he flew into the country, it was completely dark as he looked down at the city from the airplane. Carroll was given a light bulb so he could have some light at his hotel.

After World War II, the population of Romania had significantly decreased and, as consequence, Ceausescu implemented drastic measures to populate the country.

Birth control pills, condoms, abortion and any other form of contraceptive was prohibited. Doctors who were caught providing clandestine abortions were incarcerated. Motherhood became a duty, supported by Decree 770, which prohibited any women who had less than four children to have an abortion before 40 years.

Romania’s poverty increased and more children were left for state-funded orphanages. If men and women didn’t have a child after they were 25 years old, they would have to pay higher taxes. Around 100,000 children were placed in orphanages in Romania, and the number quickly grew to 400,000 children abandoned.

This massive increase in the Romanian population was more than the country could handle. Throughout his journey, Carroll captured photos of thousands of children in orphanages and the major AIDS epidemic in the country.

The documentary showed Carroll visiting an orphanage in Romania to depict the crisis the country was living in with a relief group of reporters and physicians. In the orphanage there were hundreds of babies in cribs all over the building. They couldn’t move or play and nobody had changed their diapers or fed them.

A doctor took Carroll aside to a covert room in the mortuary where he analyzed the blood of the babies that had died and noted that they were infected with the HIV/AIDS virus.

“All these children are going to die, they have HIV,” said the doctor to Carroll. “You have to tell this story in the west.”

The doctor showed Carroll perhaps one of the most horrific scenes in the documentary – the basement. The room was filled with dead babies and children. They were dying from AIDS and the doctors were not doing anything. He took pictures and ran the story at The Boston Globe.

“Romania was a life changing experience obviously, it didn’t change my life but it changed how I spent a lot of my life,” said Carroll in an interview with The Suffolk Journal. “The things that I cared about a lot when I was young I still care about, but now I have a way to actually put that caring into some kind of motion, so that there would be some result from it.”.

Carroll remembers a child with whom he had a special connection. The documentary showed some videos of the child hugging Carroll. After visiting the hospital for several consecutive days, Carroll thought of adopting him. However, when he went back, the child was not there anymore. He had been diagnosed with HIV and sent to another institution.

In response to Carroll’s photographs, families from around the world, especially from the United States, went to Romania to adopt children.

People leading the orphanages took advantage of the state of the country and as families came to adopt children, they sold babies for high prices. The documentary showed the adoption of a Romanian baby named Bethany, for whom her parents had to pay around $20,000. In other cases, families were able to formalize the adoption of a baby for around $2,000.

Although the U.S. was sending aid to Romania, they were not offering help specifically to the children. Therefore, they reached out to Carroll. Carroll was able to unite 40 people at his house where they created the foundation of RCR.

“I realized I couldn’t bring them all back to America, so my way of adopting one was by adopting them all,” said Carroll, explaining that he once thought of adopting a Romanian baby but he realized he wanted to help all the children he could.

RCR is a non-profit organization that provides help to low income families and helps to prevent child abandonment. They have volunteers in hospitals, schools, homes and they provide education, psychological and physical therapy for children and the families.

After the screening of the documentary, Carroll held a question and answer session. He also shared the story of his daughter and son, both in the audience, and their experiences in Romania and how these shaped their lives.

The organizer of this event and the host, Morelia Caron, a senior at Emmanuel College, was one of the children adopted in Romania by a U.S. family.

“I’ve always had this undeniable connection with Romania even though I actually have no memory of it within my DNA,” said Caron to The Suffolk Journal. “For as long as I can remember I had a love for the Romanian culture and the people, and I’ve been blessed with parents that celebrated and helped [me] find those connections.”

Caron found the RCR during her junior year through a Romanian friend and language teacher. Caron’s teacher knew about her special connection with Romania and how she wanted to work with children.

“I met Mike and I told him that I needed an internship for a year. It was a beautiful alignment, because I wouldn’t have wanted to do it with anybody else,” said Caron. “I’m a developmental psychological major and a photography minor, so my dream is literally what he has done, the organization and his career as a photographer.”