A swift but stark movement from the conductor silenced the orchestra, followed immediately by a tremendous roar of applause that reverberated against the intricate walls of the Boston Opera House on Sunday, Nov. 5. A simple bow was given, and then onto the “outbreak work” of “Obsidian Tear” presented by Boston Ballet. The show contrasted the stereotypical aspects of ballet, gentleness and grace, with power and control.

A performance that resurrected itself from the goddess Nyx, volcanic rock obsidian and the similarities between the two, leads the viewer into a world of pitch-black darkness and anger. A two-man ensemble began the performance of a power struggle with jolted but fluid movements, which allowed the audience to ponder the significance of the pairs’ synced motions. The difference between the two men, Patrick Yocum and Junxiong Zhao, were the colors of their pants: Yocum was wearing red while Zhao wore black.

Held in suspense of what the next action might be, the orchestra intensified the thought as the ending seemed near until a deafening note was blown and the melody continued. The two ballet dancers gracefully struggled together as both left no square foot of the stage untouched by their motions. The choreographed number portrayed the conflict as if the ballet dancers were boomerangs, constantly being torn apart, yet coming back together soon after. Conductor Daniel Stewart masterfully took hold of the performance as the orchestra controlled the ballet dancers motions, like a puppeteer directing the puppets every move.

“Obsidian Tear” was given a brief interlude where the performance switched into a second choreographed act. The dance consisted of an estimated 10 male ballet dancers who moved rhythmically in tune with the orchestra. This was expressed through a firm, powerful atmosphere throughout this installment, with the newly introduced dancers assisting Yocum and Zhao in their struggle to come out on top. Each member added to the power dynamic between the two men, exacerbating the tension. This reigned true until it appeared the dancer in red threw himself into a volcano, committing suicide and sending his counterpart into a state of grief.

The physicality of the act, and the choice for the men to be shirtless, supports the term “tear” in the title, enhancing the struggle between the two men and eventually, the demise of both. Each male tore the other apart and the added dancers in the second part aggravated the already tense condition.

“Obsidian Tear” was juxtaposed against “Fifth Symphony” in this showing by the contrast in movements, sets and the atmosphere emoted by the dancers. While “Obsidian Tear” is a dramatic, colorless and overtly negative expression, “Fifth Symphony” brought light into the second part of the performance, after the intermission.

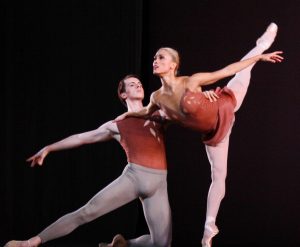

Inspired by the landscape of Finland, “Fifth Symphony” exuded a light and airy feel, accompanied by an array of pastel costumes. As partners, the female and male ballet dancers depicted a storybook fairytale. From this, a relationship is fostered between the sets and is carried through the entirety of “Fifth Symphony.”

The energetic and fast-paced movements showed the trust between the ballerinas, and was needed to deliver an impeccable performance. There was a clear difference in the movements and motions of “Fifth Symphony” compared to “Obsidian Tear” yet the unity between the performances was apparent. The jolted movements from “Obsidian Tear” contrasted with the tender motions of “Fifth Symphony” seemed to be an intentional play on the diversity of themes.

From the intense black of “Obsidian Tear” to a pastel green and pink of “Fifth Symphony,” a distinct comparison was shown in set design.

As “Fifth Symphony” transitioned into Act 2, the orchestra created a distinct ambience with the lighter notes from the flutes and the careful, simple sound from the violins. A very delicate and gentle act, “Fifth Symphony” left hope that not all is dark. The attire of the performers differed, which allowed for a dynamic performance with a different depth than “Obsidian Tear.” This depth captured the many roles of the ballerinas and the way the relationships enhanced the performance overall.

The end of the show was signaled by all the ballerinas stopped in place and the orchestra silenced, thus giving way to an eruption of applause that lasted nearly a minute. The dichotomy of the two pieces showed the profound use of different choreography, set design and costumes, and shown light on the talented ballerinas that became the lifeblood of the show.

The ballet company is set to show the two-part production of “Obsidian Tear” and “Fifth Symphony” from Nov. 3 to Nov. 12 at the Boston Opera House.