As students returned to Suffolk University’s campus this fall, posters advertising Narcan, a nasal spray which uses the drug naloxone to revive the victim of an opioid overdose, have made an arrival around the streets of Boston. These posters are just a small sign that the opioid crisis has crept its way into Boston, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the entire country.

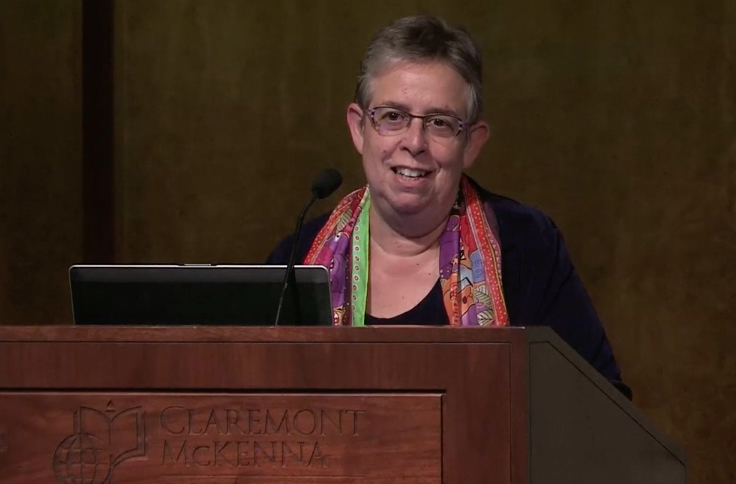

According to Suffolk sociology professor Susan Sered, there has not necessarily been an increase in drug use, but the increase in the number of opioid overdoses in recent years. Sered said these overdoses are primarily within white communities and has recently attracted the attention of lawmakers.

“The racialized war on drugs has been the mechanism for mass incarceration of people of color in the United States,” said Sered in a an interview with The Suffolk Journal “In contrast, the public ‘face’ of the opioid crisis is white and the public conversation has shifted to the need for treatment for the ‘disease’ rather than punishment for the ‘crime.”

In late September, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh announced the Personal Advancement for Individuals and Recovery (PAIR) initiative to provide financial support for low-income individuals in the early stages of opioid addiction recovery.

“You don’t fix addiction, and cure addiction, and battle addiction by yourself. It’s a community that keeps a person in recovery,” said Walsh in announcing the PAIR initiative at the Gavin Foundation in South Boston.

Walsh has worked to combat the opioid crisis in Boston by creating the Mayor’s Office of Recovery Services, which has focused on substance use disorders and addiction in the city. Since 2015, the Office has engaged stakeholders including local communities, as well as state and federal authorities.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health reported that 58 percent of patients in Boston use heroin as a primary substance, and that the use of heroin is giving way to other opioids such as fentanyl.

The Boston Globe reported in August that “fentanyl was the cause of 81 percent of overdose deaths in the first quarter of 2017.”

These types of drugs are a particularly concern for Governor Charlie Baker, who has made the opioid epidemic a legislative priority.

“This whole approach to getting a lot more aggressive about dealing with street drugs and especially with fentanyl and carfentanil,” said Baker in an early September interview with CBS, “has to be a big part of our approach at this point going forward too.”

Congress identifies the lack of professional staff at substance abuse facilities as a problem facing the United States. Pending in the U.S. Senate is the Strengthening the Addiction Treatment Workforce Act, a student loan forgiveness program for professionals who pursue careers in substance treatment.

Representative Katherine Clark (D-MA) recommended the bill in a U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Health hearing on October 11. Representatives Bill Keating (D-MA) and Joe Kennedy (D-MA) were also present to testify on the opioid crisis and offer legislative solutions.

Keating, having served as district attorney before being elected to the House, explained how he saw individuals who were prescribed opioid drugs, later become addicted to heroin. Kennedy, who also served as a district attorney, advocated for greater education on how law enforcement treats addicted individuals.

On Thursday, Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) sent a letter to Trump questioning his inaction on the opioid crisis.

“We are extremely concerned that 63 days after your statement, you have yet to take the necessary steps to declare a national emergency on opioids, nor have you made any proposals to significantly increase funding to combat the epidemic,” the Senators wrote.

Last March, Trump created through an executive order, the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, which Baker is a part of.

“This is an epidemic that knows no boundaries and shows no mercy, and we will show great compassion and resolve as we work together on this important issue,” said Trump in his announcement of the Commission.

Later, in early August, Trump described the opioid epidemic as a “national emergency.”

“We’re going to spend a lot of time, a lot of effort and a lot of money on the opioid crisis,” said Trump.

Trump has simultaneously worked to repeal the Medicaid expansion through the Affordable Care Act, which worked to provide greater accessibility to addiction treatment. Trump’s decision to not support this policy jeopardizes addiction treatment, particularly in relation to the opioid epidemic.

Sered has hope that Massachusetts will not face as many issues in dealing with opioid use and overdoses under the current presidential administration as some other places will.

“The President’s efforts to take apart the Affordable Care Act will negatively affect access to drug treatment for many Americans,” said Sered. “Locally, I am a bit more optimistic.”

Sered adds that research in the Boston area on public healthcare is active, and should be the focus for higher education institutions, like Suffolk.

“Institutions of higher education have the responsibility to teach how to access trustworthy, rigorous research. This can be difficult when the area of concern is emerging and rapidly developing,” said Sered. “Universities cannot teach students ‘the truth’ but we can and must teach students how to find and assess information.”

Steve Spiewakowski • Oct 20, 2017 at 7:30 pm

I dispute Professor Sered’s “twist”on the information from this study. “Drug use” would be any illegal substance used recreationally for mind altering purposes. Although drug use in general may not have risen substantially per capita, OPIATE use has. Consider that it is exponentially more potent than it was 10 years ago, that is highly addictive, and usually available by making a simple phone call. The number of opiate deaths last year alone exceeded the number of American casualties in the 20 year Vietnam conflict, over 60,000 in one year. Even during the crack cocaine epidemic the overdose rate with that drug wasn’t even close. The way the study is phrased trivializes the deadliness of opiates, doesn’t consider the roots in our pharmaceutical system, and needlessly draws a racial divide….

Justin mcnary • Oct 20, 2017 at 5:37 am

Having spent most of my life in and around what I guess could be called The drug culture, I can not understand how anyone can say that the rate of use has not risen. I am sure that the attention and politicization of the issue is due to the shifting demographic among users. I work in treatment and have for 5 years. We take clients from all over the country. I can ask a group what age they started using opiates and the rough average is 14. There seems to be a need to push back against this epidemic by twisting the statistics in an effort to minimize the scope of the problem. My perspective tells me we have a monumental problem that effects 3 generations, and it’s growing. I cannot equate this to anything but the AIDS epidemic in terms of public health. We are losing on the prevention front, badly. We are absolutely using inefficient and ineffective treatment modalities driven by insurers rather than results. We cannot effectively respond to the problem if we refuse to recognize it’s true scope.