The Harvard Film Archives hosted its first event of the Marginal Histories series entitled “The Films Of Pablo Larrain” in which the director was on hand to join the discussion.

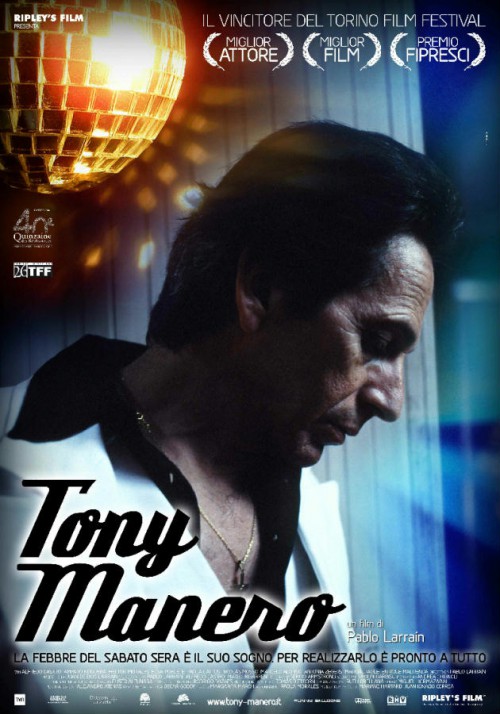

Nearly five years after its inception and Pablo Larrain’s dark and uncomfortably funny look back at Chilean society during the Pinochet regime through the obsessive Tony Manero and the film is just as fresh to view.

The film’s titular “Tony Manero” is played to a disturbingly sublime tee by actor Alfredo Castro. In the film Raul (Castro) is an aging 52-year-old forgettable peasant whose only goal in life is to transform himself into John Travolta’s Tony Manero from Saturday Night Fever. He watches the film religiously, learning the film’s dialogue and dance moves like scripture.

As he operates a small dance troupe out of a small shack of a cafe that he also resides in the troupe who are sure enough, practicing (under Raul’s Pinochet like persistence) to put on a Saturday Night Fever of their own.

To describe the scathing dark humor in the film, would give away too much of the punches that Larrain is able to pull. What is imperative to know is that Raul is a savage man, living in oppressive times. One could even call Raul madness personified, as he effortlessly goes from mercilessly beating, to cathartically dancing, to primitively having sex and back to dancing.

It is all an inglorious vicious cycle for this ghost of a man who is unsatisfied with his incomplete metamorphosis. Raul will do anything to get to his one true desire; it is his life’s work. Meaning that he will assuredly ravage whatever stands in his path, be it his own people and his own culture.

Throughout the film, we see how his exploits into the hedonistic clash with the only actual relationships in his dance troupe. Made up of Raul’s lover Cony (Amparo Noguera), her nubile child Pauli (Paola Lattus) and a young employee Goyo (Hector Morales) who moonlights as a political radical. These lost people, appear to work and live like an average dysfunctional family but as the film and time wear on; we realize everything is not bleached out skies and disco balls.

What is a testament to both the skill set of Larrain and Castro, is how this fantastic character study places you right in the depth of a sociopath as an unlikely protagonist as Raul and you still have this conflicted feeling of wanting him to win the Tony Manero look-a-like contest on the “One O’Clock Festival Show” even after you see him abandon his de facto nuclear family and leave them to feed his obsession. The film is something that must be seen.

The Films Of Pablo Larrain session in which the director was on hand talked about his film’s “awkward anti-heroes as the unlikely protagonists of a contested historic past revisited through dark, disconcerting allegories of treason, myopic idealism and the unbridled arrogance of power.”

To start the night, Larrain discussed that it was a magnitude of things that led him to create this brutal character. He claimed “That it was the position of a photograph, along with a crack head named Uncle Charlie and that the idea of having a serial killer that wants to be a dancer; that it all just came together.”

Pablo talked about how it took eight years to film Tony Manero and that he realized the dark subject matter would create a real friction with the audience. One of the main themes in the film, is the “Chilean absorption of American culture, to phase out issues in the country.”

Larrain would go on to notice how the film creates a final product that is equally “dark, funny, and sad.” Another motivator for the film’s plot was the fact that “most of the regular crimes would go un-investigated.” There was rampant impunity and they would only be looking for political rebels.

Larrain realized that his film would cause much controversy upon its release and remarked, “I realized that it’s very uncomfortable on both the right and left wing politically. ”

“It creates a lot of internal friction. People would ask, why are we showing this disaster to others (referring not only to the film, but the era of despair in Chilean history)?” He could not believe that “the critics were looking for redemption” for Raul. Happy with the polarizing effect, he agrees that the film has a “restlessness and anxiety that lives in the film and that it’s all about the plot and the atmosphere.”

Being a rare treat to see the film on 35 mm, he laughed and said that this was made during a time where “you could buy film and make a movie and no one would call you crazy.” Echoing that the film’s spooky atmosphere is due in part to expired film stock that he bought from Canada. He felt compelled to make this film because no one would talk about the Pinochet years, “they would talk about ’73,’74,’75 but then they would jump to ’82 as if nothing happened.”

When asked about the off centeredness of his films, with people mostly living on the fringe, he stated that it was ”A chronological impact, that Saturday Night Fever had played for eight months and that over one million tickets had been sold and that these people are forgotten by everyone and that no one understands them,” adding that Raul himself was most likely illiterate.

Thinking that getting the right to not only Saturday Night Fever but Grease as well. He mentioned that “we had already filmed the movie, but John Travolta and Paramount were both very helpful and that Travolta personally signed off on it. Pablo mentioned that the old world of Chile is now gone.

That old world culture aspect is gone and that he had “a lot of interest of looking back at something that couldn’t be looked at.”