Diego Zambrano Journal Contributor

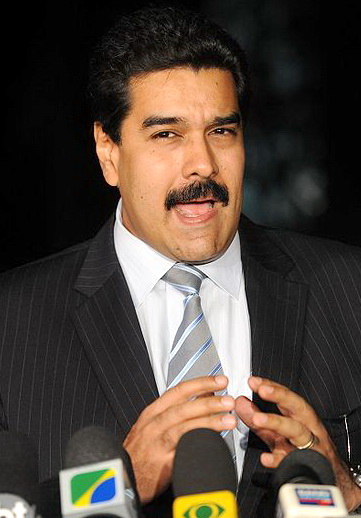

“This 5th of March, at 4:25 p.m., the commander president Hugo Chávez Frias has died. This is a historic tragedy.” Those were the exact words of Vice President Maduro announcing to the Venezuelan people on a national broadcast that Chávez passed away. After almost three months without seeing our president, the government’s news was both shocking and unexpected. The fact is that, as said before in these same pages a few weeks ago, all the evidence pointed that Chavez’s health was precarious. But regardless of what we thought about the president’s condition, the confirmation of his death shocked the country.

On the one side, those who opposed Chávez could not avoid feelings of relief when seeing this news of the man who prosecuted, incarcerated, intimidated, and epilated anyone who spoke openly against his “revolution.” On the other side, those who received any benefit (disregarding how miserable it could be,) felt stroked about his commander-in-chief leaving this world.

His followers, mainly because of the government’s constant reports stating that Chávez was getting “better” with a lack of real information, truly believed that the president was going to come back to take office. Local polls showed that nine out of ten of Chávez’s followers interviewed believed that he was coming back.

But the main shock about Chávez’s death differs from whether one is a “Chavista” or not. The country and its institutions lived the last 14 years under the overarching figure of Chavez. He was an authoritarian leader who not only prosecuted opposing leaderships, but also stopped any emerging leadership in his own party. This leaves a huge vacuum in the country. The executive power, as well as the legislative and judiciary, worked under Chávez’s rule and guidance. Thus, what comes next for the country is definitely difficult to project.

The Constitution says that elections must come if the president dies, and the National Electoral Council (CNE- the highest electoral authority in Venezuela), established the presidential election for April 14, 2013. Both Chávez’s party and the opposition already started campaigns. On the opposition side, former presidential candidate against Chávez and current Governor of Miranda, Henrique Capriles Radonski has been chosen to run once more in less than a year. On the Chavismo side, Vice President Maduro is running for office. It is necessary to point out that Maduro is also the Transitory President, a fact that violates the Constitution, but since the judiciary is openly politicized in favor of Maduro, he has been allowed to run.

Chávez appointed Maduro as his successor in his last TV broadcast in Dec. 8, 2012. But it is obvious that Maduro is not Chávez; in fact, he does not seem to be able to win an election. The only powerful tool Maduro has is the memory and shadow of Chávez. Since Chávez died and the campaign started, Maduro has named Chávez more than 2,500 times; showing how dependent his candidacy is on the death of the “supreme leader.”

The country will suffer no matter who wins. If Capriles overcomes immeasurable corruption in the election and reaches the presidency, he will have to rule with a parliament against him, a judiciary in favor of the Chavismo, and Armed Forces that have openly said they support Maduro and will do “anything to take him into office.”

If Maduro wins (which seems logical due to the illegal advantage he has – public funding, government money, unlimited TV and radio exposure, the CNE on his side, the Armed Forces openly declaring in favor of him, etc.,) I do not see how he can maintain the system as it is right now. He does not have the charismatic power that Chávez had, and there is not enough leadership in the Chavismo (due to Chávez not allowing anyone to grow) to successfully share the burden of the problems attacking Venezuela now.

The rumors about Chávez’s health finally came to an end with his death, but the questions about the future of the country just started. No matter which party takes office, without a figure like Chávez concentrating the powers that have been accustomed to being centralized for 14 years, the future of the country is a rocky path. Venezuela will suffer changes, and Latin America too, because the shadow of Chávez’s absorbing figure will soon be followed by a vacuum that will hopefully be filled with institutionalization and democracy, not another Chávez.