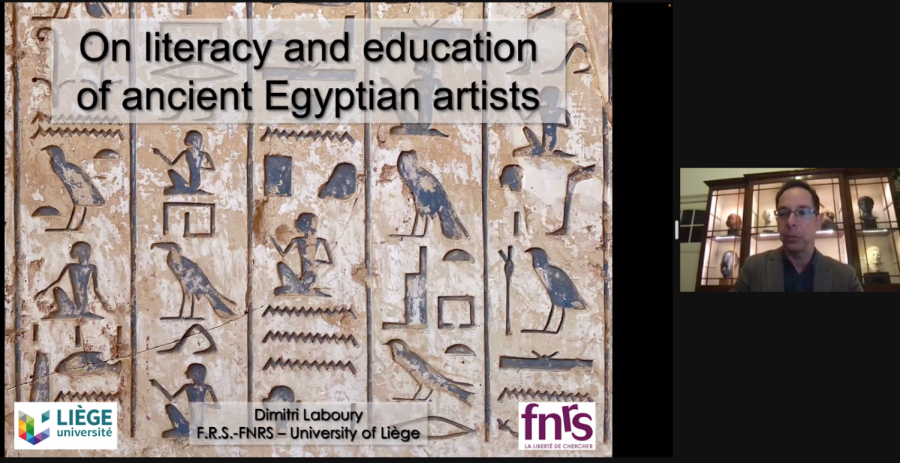

“Reading the hieroglyphs defines, nowadays, Egyptology,” said Dimitri Laboury at The Harvard Museum of Science & Culture webinar, “On the Literacy and Education of Ancient Egyptian Artists,” Thursday, about 200 years after hieroglyphs were first deciphered.

Hieroglyphs were used 31st century B.C. to A.D. fifth century.

Laboury, the research director at the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research in Ancient Egyptian Art History and Archaeology, introduced hieroglyphs as a complex writing system and expanded on the relationship between ancient Egyptian artists and written culture. He also spoke about who could actually read hieroglyphs.

Laboury revealed most of the people who actually painted the inscriptions might not have always been able to read them. Mistakes were sometimes made in inscriptions because there were misunderstandings with the transcripts.

Scribes were taught to write in tachygraphy, a shorthand form, and then maybe hieroglyphic writing.

Oftentimes, self-portraits would show up in hieroglyphs as a way of the artist introducing themselves. Being an artist in ancient Egypt was seen as a respectable position, similar to scholars.

The Irtysen Stela, now at the Louvre Museum in Paris, shows an artist describing how hieroglyphs were a restricted level of literacy.

“The artist explicitly said that he knows he was introduced in the secrets of the hieroglyphs,” said Laboury. “This is the first competence he wanted to show off, and then, through the structure of the stela introduced by a specific sentence in ancient Egyptian, which means ‘it’s a fact that I know.’”

In one tomb, which belonged to a Palace of Truth’s servant, many grammatical errors are seen on the wall inscriptions. The hieroglyphs were written by the servant’s son.

“When I presented this case to my students the first time they told me is really stupid,” said Laboury. “‘This guy could not write,’ and I told them, ‘No, [you] are completely wrong. He was a genius because he learned to write and read hieroglyphs by himself, because he knew some hieroglyphs from his visual culture.”

Names in tombs were frequently left as blank spots because people would not know the names of the family members of the deceased.

‘Rough drafts’ on stone tablets were found in the trash that belonged to the artist. They would have to readapt the text to fit the wall. Laboury explained how this particular painter was able to read such a draft and transpose it onto the provided space.

“I would like to remind you, that we know nowadays that this is how our own alphabet came to life,” said Laboury.

Suffolk University history professor Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik shared the same sentiment.

“The ancient cultures of Egypt and the Sudan are foundational to European and American cultures today. In many ways you could say that the cradle of writing culture rests in what would now be Egypt and the Sudan, as well as Mesopotamia,” Tolan-Szkilnik said.

That should push us to view Egyptian and Sudanese civilizations with the same reverence we portray Greek or Roman civilizations,” she said.

The event was sponsored by the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East and was part one of three in a lecture series taking place through the semester. The next two webinars will be held on March 31 and April 21.

“It’s me the stone who writes correctly and make his name life again, but by writing that is the one who writes correctly, he made a lot of mistakes, and so my kitchen was able to show that he does not 18:40:46 know the principle of hieroglyphic writing, but only mono consonants, and science, that is, the alphabetic signs of orographic writing.”