Historians discussed Massachusetts’ dark history of slavery and racial injustice at a panel on Feb. 18.

This panel was part of a five-part series hosted by the Massachusetts Historical Society and Northeastern University Law School’s Criminal Justice Task Force. Moderator Jared Ross Hardesty, an associate professor of history at Western Washington University, opened up the panel by asking speakers to analyze what it means to confront the wealth Massachusetts and New England have that was derived from slavery.

Guest speakers Dr. Nicole Maskiell, assistant professor of history at the University of South Carolina, and Elon Cook Lee, director of interpretation and education for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, highlighted Boston’s dark history with slavery and the North’s tendency to dismiss that it ever existed here.

Maskiell described her experience as a student at Harvard when it came to unpacking Boston’s history with racial injustice — from the streets named after slave owners to family legacies at Harvard that trickle down from plantation owners. She recalled hearing stories of executions of enslaved people and members of other marginalized communities on the Boston Common or other local public spaces such as the executions of Mark and Phillis.

She explained that, despite living in the Cambridge area for nearly 10 years, she did not realize the extent of which slavery impacted the state.

“I didn’t really know that New England had anything to do with slavery, except for being the kind of promise land… the place people would run to and be sheltered,” she said.

The panel largely focused on the erasure of the history of slavery throughout the U.S. and how it has contributed to modern-day racial injustice. Lee spoke about how the conservation of history has often led to purposeful redirection when it comes to a historical figure’s entanglement with the slave trade.

“A lot of it [historical erasure] is just the way we story-tell about different individuals from histories and different parts of history, because we want our kids to look up to [historical figures] and our kids shouldn’t look up to people who were violent or were okay with violence happening in their name,” said Lee.

She added that the preservation of George Washington’s Mount Vernon home and plantation was influenced by members of the Confederacy, which ultimately contributed to the erasure of Washington’s participation in slavery in many modern contexts.

Maskiell then explained how slave owners were paid reparations for losing slaves once it was made illegal to own enslaved people, and the role this has played when looking at contemporary racial injustice. Much of the money from those reparations went into endowments at universities and other investments, giving prominent families wealth while people of color were not compensated.

Both speakers agreed that, in general, slavery has notoriously been viewed differently in the South than in the North.

Maskiell spoke about how often people differentiate between the types of slavery, and how those differences were seen geographically. She explained that while traditionally slavery in the South was reduced to growing cotton and other manual labor, slavery in the North often consisted of waste removal and indoor work.

This, along with the historical story-telling Lee mentioned, contributed to New England being seen as exempt from participation in slavery, Maskiell said.

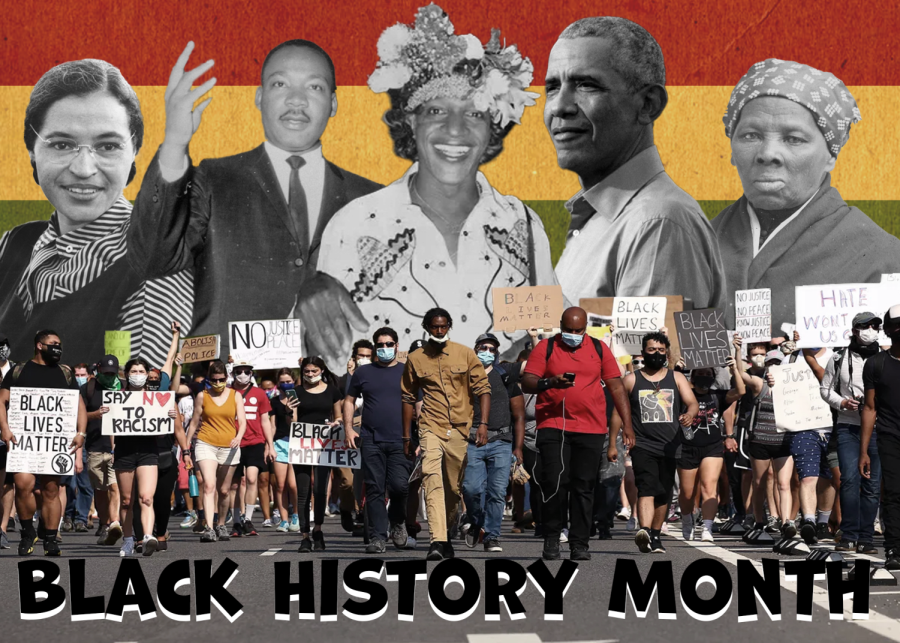

Criminal justice reform has been brought back into the spotlight following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and many other people of color. The panelists spoke about the role that acknowledging and valuing history can play in rethinking how law enforcement operates.

“The more information people have, the more that does help to break down some of the stereotypes that are in people’s minds,” said Lee. “You have to make sure that you’re building policies in place that take into account the history, not just the history of policing but the history of the community.”

The panel closed with a Q&A from the audience, discussing various aspects of generational wealth, segregation and upholding famous Black individuals.

Lee spoke on generational wealth in terms of race, explaining that while immigrants and Black people had often started out in the same lower-class neighborhoods, white immigrants were able to work their way out and into a place of economic comfort, while systemic racism barred Black people from doing the same.

Maskiell spoke about “token Black people” that are often seen as exceptions to this rule, and how normalizing famous Black figures allows Black people to fit into the nation’s history.

“I’m interested in the… ordinary individuals and what they did on a day-to-day basis because it really normalizes, I think, the place of Black people of all backgrounds, of all abilities, of all interests,” Maskiell said.

“When we focus in on the ‘special’ Black people, we kind of put them on a pedestal and they’re shaved of any imperfections… anything that makes them not a very idealized human,” said Lee. She continued by adding that stripping historical people of color of their glamorized story-telling makes them more relatable for everyone, and can encourage change in the modern world.

Follow Shea on Twitter @ShealaghS.