This article makes frequent reference to delicate mental health issues. Please read at your discretion.

I have but once never used first-person in my three years at The Suffolk Journal. I stress to writers all the time that the only occasion in which you should invoke your experience in an argument is if it is essential to the story you are telling. Today, for me, it is.

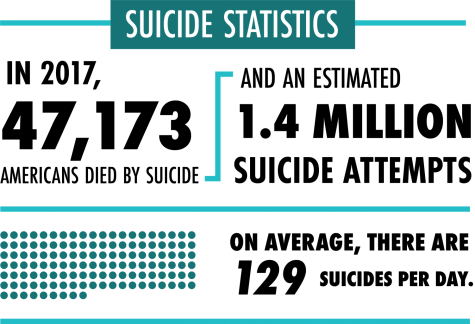

September is, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), Suicide Prevention Awareness Month. I don’t identify as an expert on how the whole “fill-in-the-blank Awareness Month” thing works, but it’s my general understanding that the goal of such a month would be to start a discussion about the issue at hand, in turn raising awareness of it.

My illness, borderline personality disorder, has a suicide rate of nearly 1 in 10, according to Psychology Today. Every part of my relatively new life has been touched by it. The lives of everyone I love have been touched by it. And it is my well-educated guess that many of you have been touched by it, too.

But no one really wants to talk about suicide. They will talk around suicide — cite statistics, warning signs, et cetera — but almost never about suicide itself.

That reluctance to discuss suicide is understandable. Suicide is one of the most complex and misunderstood issues, chiefly because it defies what we know about human behavior. There are so many warning signs and as many explanations, and almost all suicides occur for mental health reasons, according to NAMI. But that isn’t always evident to onlookers.

The human being is endowed with a wild sense of self-preservation. It is at the same time, relatively speaking, incredibly reasonable. Suicide challenges both that sense of self-preservation and the sense of reason. How can anyone have a reasonable conversation about something that at its core defies traditional reason?

Faced with that impossible task — rationalizing and reasoning with the irrational and unreasonable — we instead retreat from it. When confronted by suicide, we do what we do with the majority of truths we don’t want to face: we look the other way.

On those rare occasions when we as a society do discuss suicide openly, the conversation is at best a superficial, ignorant effort, and at worst exacerbates the issue. There are actors and actresses raking in millions per season for their roles in “13 Reasons Why,” a Netflix series chronicling a romanticized suicide that mental health professionals at NAMI have condemned as offering “a dangerous perspective.”

Other human beings profiting off of what amounts to suffering porn — and then sleeping comfortably in a loft in TriBeCa after their day playing make-believe with other people’s tragedies — is one of the most despicable things I have ever witnessed. It does nothing to advance any healthy discussion. But that’s a conversation for another, far more contemptible op-ed.

Instead of discussing suicide solely when it is convenient — when it pays the condo association or trends on Twitter — we have to have a consistent dialog about what suicide really is, how it impacts those who are touched by it and how we can show people that there are other ways out. More importantly, we must educate people on how to help.

There is always a place for medical intervention, whether that be in the form of inpatient hospitalizations, medication or continued psychotherapy.

But often, for lack of access to treatment or fear of stigma, those who are experiencing suicidal ideation don’t reach out to professionals. Instead, they tell a friend, family member, coworker, or someone else with whom they are intimately acquainted. It is a situation none of us want to find ourselves in, but it happens and happens often.

I am not a doctor nor should anyone treat my perspective as medical in nature. But in my experience, both with myself and with others, the suicidal mind is desperate for reassurance that the emotions it is feeling are real. Sometimes, it’s as simple as offering that reassurance.

Yes, your pain is real. We see it. And we can get you through it. The best advice I can offer on the subject is to, after ensuring immediate safety, start there.

When it comes to something as daunting as suicide — and mental illness as a whole — it can often feel like onlookers are powerless, as if they are driving by a fiery wreck and all they can do is watch the first responders work against time.

People as average as you and me are the first line of defense against suicide.

There is hope beyond suicide, but only if we’re willing to talk about it and do something to address it. We should’ve realized this decades ago, but for many, it isn’t too late. We can do something about suicide. It finds its beginning and end in us.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide or self-harm, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK.