Heroin haven and drug reform

November 18, 2015

The United States has the highest incarceration rates in the world. Drug use is increasing, as is the number of overdoses. So what’s the alternative to the current state of the drug war?

To get the answer, we need to shift our focus from recreational legalization to the urgent problem in front of us.

Taking a bold step away from the ever-failing war on drugs, the non-profit Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) announced on Nov. 3 their plan to open a haven for heroin addicts.

This haven will be a clinic where drug users can ride out their high under medical supervision and receive treatment, if they choose. This program views addiction as a mental health issue, not a crime — a notion we all ought to take into consideration.

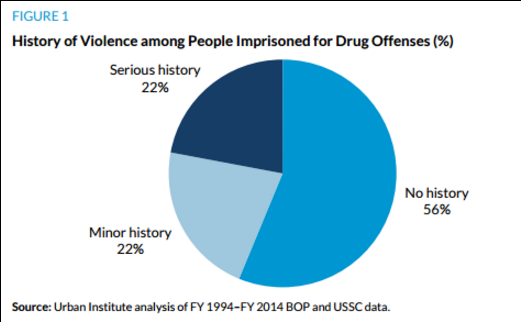

U.S. drug laws label addicts as untreatable criminals who deserve punishment. If we want the rest of the country to follow in this program’s footsteps, we need to shift our focus from legalization of recreational drug use to helping those who are really suffering.

Dr. Jessie Gaeta, the BHCHP chief medical officer, hopes the haven will reduce the number of overdoses, which often occur because the user is using without access to adequate care. This approach comes in the wake of the heroin epidemic in Boston that seems to be steadily getting worse in the last decade.

It should come as no surprise to any Bostonian that the homeless problem in the city is severe and that opioid addiction is part of the problem. Moreover, a 2013 study by the BHCHP and Massachusetts General Hospital revealed that opiate overdose has become the leading cause of overdose deaths among the homeless, accounting for 80 percent of deaths.

The Center for Disease and Prevention reported that heroin use nationwide has more than doubled over the last ten years, and overdose-related deaths have risen nearly fourfold. Clearly, our drug policies — which have changed little over the last 35 years — have not only failed, but have also caused more problems than the ones they were supposed to solve.

At this point, it seems that most Americans agree that something needs to change. According to a study by the Pew Research Center, 67 percent of U.S. citizens believe that the government should

provide treatment for users of “hard drugs”, such as heroin or cocaine.

Yet the public officials who actually control drug policy are not convinced — and there’s a reason for that, paradoxically, because it puts anti-drug war activists at fault. Among the “most Americans” in favor of reform, the most vocal group are the activists fighting for legalization of recreational marijuana.

Yes, I believe consenting adults should be able to decide what they put in their own bodies. But is this really the most important drug-related social issue we are facing? We need to put the libertarian-based argument aside and focus specifically on what matters most right now: saving the lives of thousands of addicts across the nation. We need the policymakers to think “It saves lives” when they hear the phrase drug reform, not “Oh, another stoner who just wants to smoke all day.”

They may be wrong to jump to that conclusion, but the fact is they do, and the only way to change that is by changing the focus of drug reform. If, as a nation, we want to begin thinking about sensible drug policy, then recreational marijuana legalization activists need to lose the spotlight.

Legalization alone won’t solve a thing. What’s much more important is the re-allotment of the more than $50 billion we spend annually on enforcing the drug war to treatment efforts and the shift from viewing addiction as a crime to viewing it as a public health issue.

We can learn a few things from watching how BHCHP’s plan will unfold right here in Boston. A similar initiative in Gloucester has already proven fruitful. The police department announced that if addicts walk into the police station with their drugs and needles, they will not be arrested. Instead, the police will immediately begin working with them to get medical care and addiction treatment.

Leonard Campanello, The chief of police in Gloucester, said that since the implementation of this program in June, there has been a 23 percent decrease in shoplifting, breaking and entering, and larceny. Police departments in several other states are beginning to try this approach as well. Addicts are real people, and they need our help.