Arfat “Alfred” Erkin had not heard from his mother back home in China for two years. He feared the worst, believing she, like so many other Uyghurs [WEE-gurs], had been taken to a re-education camp in Xinjiang.

Erkin was studying economics at college in Maryland since 2015, when he learned of his mother’s fate. He could not understand why his mother, a mathematics teacher with 30 years of experience, could be taken away. Ever since, he’s been an outspoken advocate on social media for the release of all Uyghurs.

After learning more details about her disappearance, Erkin learned that as many as 11 of his other relatives, including his father, had been detained, interrogated or imprisoned in Xinjiang camps, along with an Amnesty International estimation of 1.5 million other Uyghurs.

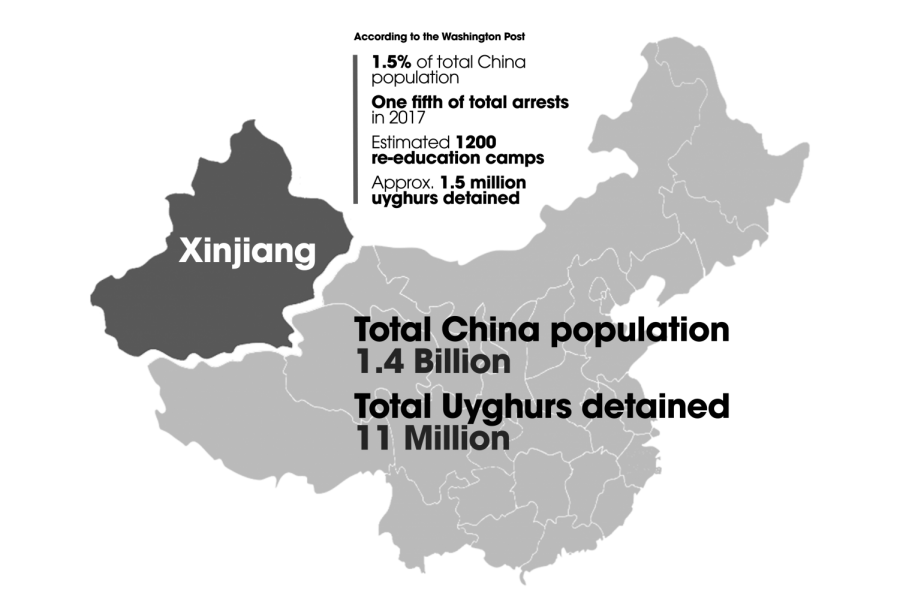

The Uyghurs are an ethnic Turkic-speaking and predominantly Islamic group spread throughout East and Central Asia. An estimated 11 million, the largest concentration, reside in Xinjiang or “New Frontier.”

Just about everything about Uyghurs, separates them from their dominating counterparts — the Han Chinese, who make up 92% of China’s 1.4 billion population. The Uyghur language is closer to Turkish than it is Mandarin and, physically, its people look more European than Asian. However, one of the biggest distinguishing factors is their religion. The majority of Uyghurs are Muslim, a practice that is becoming increasingly restricted in China, an atheist state.

The Chinese government began an anti-Islamic radicalization campaign following the September 11 attacks in New York City in 2001. There was then a significant escalation in pursuing suspected terrorists in China beginning in early 2017. Most of those targeted were almost exclusively Uyghurs, according to the Human Rights Watch.

Many times when someone is arrested for suspected terrorism their own families are not informed, like in Erkin’s case.

He only made contact with his mother this past September with the assistance of advocacy groups and the United Nations (U.N.).

While Erkin was happy to find that his mother was still alive, he noticed that something was different about her now. In an interview with The Journal, he explained what little information he learned about her from a statement by the Chinese government.

“I don’t know what the hell happened to my mom in the camp,” said Erkin. “but she had to have a very big surgery just following her release. She can barely walk right now.”

The statement included a chilling video of his mother telling him to stop spreading lies about the government and not to create a terrorist organization.

Erkin found this preposterous, he had not even spoken with her for two years. Nor was he in anyway involved with terrorism.

“She appears for like 16 seconds in that propaganda video,” said Erkin. “She wasn’t even standing, she was leaning towards the [camera].”

On Nov. 9, Erkin received another response from the Chinese government. This time he found it was even more convoluted and alarming. He was told that his father, a journalist with many government-awarded accolades, had been imprisoned. Their reasoning was not definitive at first, but Erkin eventually discovered he was arrested for being a terrorist and is now serving a sentence of 19 years and 10 months.

The Chinese government claimed his father confessed to multiple crimes including terrorism. They even declared Erkin himself a terrorist and a liar, saying he made up the story about his mother’s incarceration, contradicting the video he received in September.

Ronald Suleski, a Suffolk University professor and Director at the Rosenberg Institute for East Asian Studies, has spent years all over Asia. He explains the Xinjiang re-education camps differ from the Nazi concentration camps of the 1930s and 1940s, but are not to be treated differently from the international community. He spoke to The Journal about the camps and China’s plans to modernize its less developed provinces like Xinjiang.

“It is more like a big campus of some kind, except you go through the fence and somebody checks you into a dormitory with other people,” said Suleski.

There are no reports confirming mass genocide, but prisoners have been subjected to brutal conditions, beatings and what appears to be an erasure of their Uyghur culture.

“What the Uyghurs believe in is considered, by Marxist thinking, feudalistic superstition, it keeps people down, it keeps people poor,” said Suleski. “It restricts their chances for education and does not equip them to go out in the world to do a lot of things.”

China is being careful according to Suleski, “They want foreign money to come in, they want tourists to come in. They want to keep this whole thing quiet.”

The Global Times, a Chinese Communist Party affiliated tabloid, refers to Uyghur prisoners as “trainees.” They report prisoners are enrolled in Mandarin, law, vocational and courses that aim to eradicate extremism.

“You listen to lectures about the government and why you should believe the government is good,” said Suleski. “The problems are that when the Chinese are in control… they can do anything.”

Advocacy groups including the Human Rights Watch and the U.N.Human Rights Council have called for the camps to shutdown and the prisoners to be released. However, China would prefer for the international community to not meddle in their internal affairs.

“They want to re-educate you and turn you loose as a loyal Chinese citizen that supports President Xi Jinping,” said Suleski. “It’s a big plan to reorganize, for the purposes of control and guidance of Uyghur society.”

China annexed Xinjiang in 1949 and Tibet in 1950, increasing their land size tremendously. The mostly mountainous, sparsely settled regions are now seeing Xi’s modernization effort.

China is an emerging superpower; the nation with the largest population and the fastest growing economy, according to the World Bank. In 2018, Xi announced plans to transform China into a “great modern socialist country” by the mid 21st century. However, groups like the Uyghur pose a threat to his vision.

“They want a society where people don’t feel the need to yell at the government to make changes, to challenge the government. Where the people will make money to work, travel and have a good life,” said Suleski.

Aside from advocacy groups, the world is largely silent to the situation in Xinjiang. Social media has allowed for information to trickle through to the outside world, but many in China do not speak of it, lest they get into trouble themselves.

“They’re afraid to speak, because if they are overheard by someone who reports them, they’re in big trouble,” said Suleski. “Sometimes they do speak out, but they don’t want to ruin their career, they don’t want to go too far.”

Erkin cannot do much but talk to the advocacy groups. He does not risk talking to his family directly.

“I still have my siblings and my relatives [in Xinjiang], I don’t want to cause any trouble for them,” said Erkin. “If I contact anyone, they may get detained, so I did not contact my other relatives to get information about my parents.”

Erkin says that the Chinese government is working to erase Uyghur culture outside the camps as well. “They are destroying thousands of historic sights and buildings,” said Erkin. “Rewriting the history.” Using satellite technology, The Guardian reports that dozens of religious Uyghur sites have been heavily damaged, if not destroyed.

With modernization comes the necessity for control. Xi is updating security technology all over the country. The Hong Kong based, South China Morning Post reports that China is implementing mass surveillance, face-recognition scanners, the infamous social-credit system and even robotic birds.

All these security measures will help secure the new trade project Xi has promised, the Belt and Road Initiative. The Council on Foreign Relations explained that this plan calls for unprecedented projects of highways, railroads, pipelines and more that span westward, passing through regions like Xinjiang. The Uyghurs and their culture pose a threat to Xi’s plans.

He knows that one of the only ways to stay in power is to have loyal citizens. Those who are not loyal will be forced to be loyal. Suleski says there is not much the international community can do about this. China’s immense power and influence allows them to do whatever they want, “It’s part of the whole re-education effort. Re-education equals control.”