“Rights are like your muscles; if you don’t use them, you lose them.” That’s how Mary Beth Tinker, a youth rights and free speech activist opened her talk at Suffolk University Nov. 15.

In 1965, at age 13, Tinker wore a black armband to her Des Moines, Iowa middle school to protest the Vietnam War and show her support for peace. Her brother and several friends wore the same armbands to high school. When the unsympathetic school board heard of the students’ plan, they warned them to remove them or face suspension.

Defiantly, the students refused to follow the board’s orders and were suspended. With the help of Iowa’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Tinker’s family sued the school district. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the justices ruled that Tinker was protected by the First Amendment, and voted 7-2 in her favor.

Since then, Tinker has led a relatively quiet life as a pediatric nurse and an advocate for free speech and youth rights. She visited the Law School in part to speak to high school students in Suffolk’s Marshall-Brennan Constitutional Literacy Project.

Tinker was the daughter of an outspoken Methodist minister who preached against the racial injustice in America, and travelled to Mississippi to protest the mistreatment of black Americans.

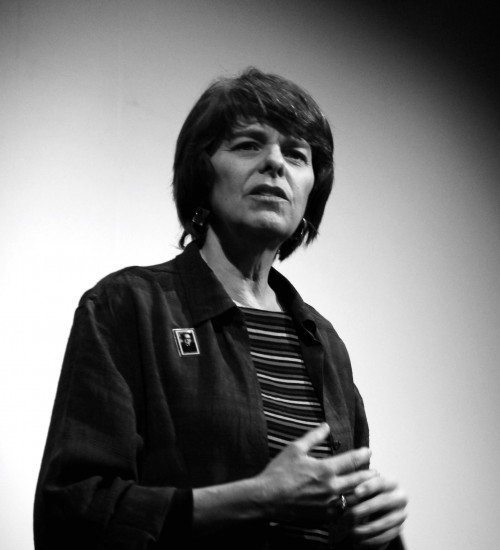

(Photo by Flickr user Andrew Imanaka)

“My father was kicked out of one church for standing up for what he believed in,” Tinker said. “I learned to stick up for what I believed by watching my parents, and learned from their courage.”

Tinker was moved by the television footage of Southern black youths getting sprayed by fire hoses for standing up for their rights.

“I grew up in a time a lot like today… [when Americans faced] issues like pollution, racial inequality, the Vietnam War and the war economy. The marriage rights issue of our day was fighting against the ban on interracial marriage,” Tinker said.

While she said she had little courage as a young girl wearing the armband – which she took off without a fight as soon as the vice principal asked – she developed firm convictions as she got older. Her family’s support of peace led them to convert to Quakerism after the trial.

Today, she talks like a preacher, sure of herself and her beliefs, and wanting the whole room to stand with her against injustice. Her activism has drawn opponents, but Tinker does not find them threatening.

“I love it when I get hate mail,” Tinker told the laughing audience as she showed a picture of the red hammer and sickle her family had received during the Tinker v. Des Moines trial. “I don’t understand why they thought [my family] were Communists,” but it didn’t scare her away from her activism.

She reminded students in the audience that “young people have the power to lead and better people’s lives and their communities” when they stand up for what they believe in, and encouraged them to make use of their rights-defending muscles.