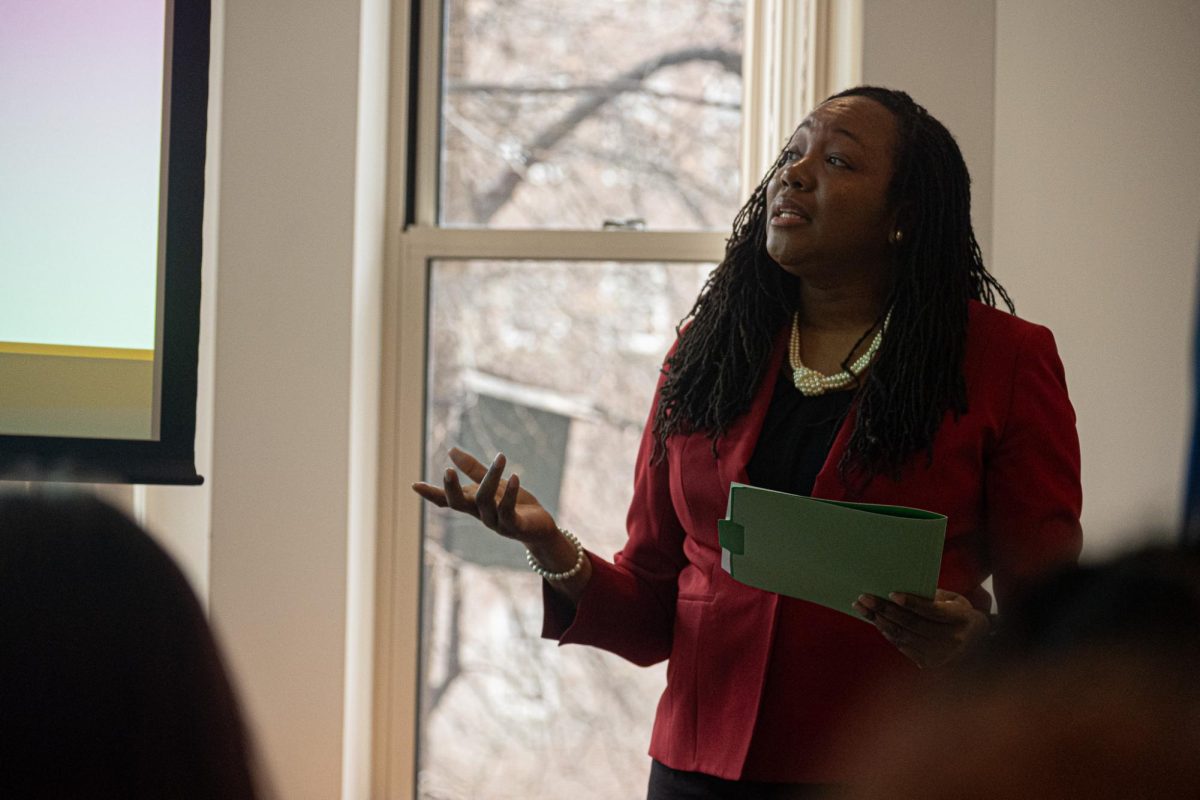

Boston’s first Black Police Commissioner William G. Gross spoke to Suffolk’s Black Student Union (BSU) on March 26 about what it takes to lead Boston away from rampant racism.

“It’s such an honor to be here in this capacity,” said Gross to BSU. “A lot of people died for me to be here in this capacity; a lot of people of different ethnicities.”

Gross, who was born on Feb. 1, 1964 and raised in a poor farm town in Maryland before moving to Dorchester when he was a teenager, has been a member of the Boston Police Department (BPD) since he was 18 years old. After passing his police certification test with a score of 99, Gross has risen through BPD’s ranks and seen firsthand the adversity that comes with being a person of color in Boston.

“We have a rich negative past, being known as one of the most racist cities and one of the most racist police departments,” said Gross.

Gross said African-Americans sued BPD for unfair promotional and hiring practices within the department, which had been dominated by Irish-Americans for decades, shortly before Affirmative Action was enacted in Boston in 1974.

He also spoke about the assault of a Black man in City Hall Plaza during the bussing riots in the 70s, how Black Red Sox players were regularly called the n-word at Fenway and anti-police sentiment within communities of color.

“Why is there anti-police sentiment? You know why,” said Gross. “Negative interactions where people suffering from poor socio-economic statuses, people of color, have incidents where Black and brown men were being shot, as well as caucasians, if we’re telling the truth.

“Some shootings were justified. Some weren’t. But the perception is there was a lot of explaining that needed to be done [but wasn’t],” said Gross.

Knowing this as a commissioner, Gross said BPD and the city should be studying and learning from any incident like this in other cities and states.

Gross also said BPD should be transparent about shootings, especially if they are deemed justified by the force.

“Long story short, the culture of Boston police was not that of sincere servitude,” said Gross about BPD’s actions throughout the 20th century. “The culture was how many arrests can you make, how many traffic citations can you issue and don’t take [anything] from anyone, we’re the police. There was no community police, even though that was taught at the academy.”

Gross said police officers used to have to meet ticket and arrest quotas at the end of each month, however, this is not the case for BPD today. Instead, BPD keeps computer statistics on Part 1 offenses, which include homicide, rape, aggravated assault and other high level crimes, in order to track the crime trends in Boston and if BPD officers are doing their job correctly.

Each captain of Boston’s 11 districts regularly presents these statistics to Gross, who said each captain “must have an answer for every statistic.”

However, Gross said any shift to a more cooperative and fair culture within BPD did not happen until after crack cocaine became popular in the 1980s and homicide rates rose dramatically in the 1990s. This crisis, said Gross, was only getting worse because communities were filled with tension and both law enforcement and the rest of the judicial system were not sharing information or their priorities with the public.

“[Crack cocaine] destroyed almost every family that was associated with it,” said Gross. “Then from 1990 to ‘94, 40 to 60 [Black teens] were being killed in the streets of Boston. Then we started losing the city because it was such a lucrative profession to be a drug dealer… The gangs of Boston were no joke… No one seemed to [care] until our homicide rate hit 152 to 154.”

Once the police, courts and probation finally began cooperating with each other while starting to work with community stakeholders and the private sector to create new initiatives and resources for those at risk, the city began to improve.

For the next two and a half years after this change began, no teens were killed and Boston’s crime wave plummeted, Gross said.

Gross said BPD has continued to support at-risk youth and struggling individuals through numerous community and intervention programs; a trend he looks to continue. But even with this change, Gross said there is still a long way to go.

“I’ve had family members who were at the scene of their loved ones getting killed and they say ‘I’m not [coming forward]’ because they don’t trust the system,” said Gross. “You’re not going to get trust overnight. It takes a long time and you have to have discussions like this.”

Justine Morgan, president of Suffolk’s Black Student Union, said she hopes BPD will have more casual interactions with minorities and Black youth, such as holding events in the Boston Public Schools where officers are dressed in everyday clothes. This way, she said, the police will induce less fear into the community.

“They should come to these events not as cops but as themselves,” said Morgan. “There should not be an invisible barrier between the cop and the community [that is created by the uniform]. In these types of events, there is no sense of ‘superiority’ from a cop, instead, everyone is talking and coming together as one.”

Gross said he owns up to BPD’s racist history and wants more people to talk about it and the people that it hurt as a result. Otherwise, he said his department would have no legitimacy.

“Tell the truth and then you can compare and contrast,” said Gross. “Then you can say we’re not like that now, there’s been a cultural shift, because people are better educated, better trained, and society is more accepting of people of color in many different roles now.”