Italy’s parliament has finally chosen a prime minister to govern a changing political landscape more than two months after inconclusive national elections left the country leaderless. General anger and annoyance from Italians was the overriding public sentiment as political players struggled to come to agreement. But now, even after a government has been set up, some extremists in the country are acting out.

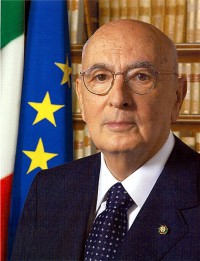

Reuters reported earlier this week that a suspicious white powder and written threats to President Napolitano and Silvio Berlusconi were sent to the Milan headquarters of the national newspaper Corrire della Sera. Another package and threats were sent to the Milan headquarters of the daily paper Il Giornale, which is owned by the Berlusconi family, according to Reuters. Threats were signed by the “Armed Group for the Defence of the People.”

Earlier in April an anarchist group claimed responsibility for sending a defective parcel bomb to the Turin headquarters of the newspaper La Stampa.

Without a single party or coalition controlling both houses of parliament, Iawmakers could not select a prime minister or a new president immediately in February. At the beginning of this month, newly reinstated President Giorgio Napolitano asked Enrico Letta to be the Prime Minister representing a reorganized center-left coalition.

Italian citizens, who had been eager for a new government since former Prime Minister Mario Monti announced plans to resign in December 2012 after Silvio Berlusconi and the People of Freedom (PdL) called for a vote of no confidence (a very common practice invoked in Italian politics to drive out leaders), have waited anxiously as their political leaders attempted to hash out a plan for the government.

Italians’ excitement during the election season, which saw primary elections (a very new part of the Italian election process) cropping up as early as November for a national vote originally set for April, was put into overdrive after Monti’s announcement. While Monti’s technocratic government arguably saved Italy’s economy from destruction, its austerity tactics were extremely unpopular.

In the February national elections the two major coalitions, Pier Luigi Bersani’s center-left coalition called Italy Common Good (IBC) and Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right coalition headed by the PdL, were shaken up by a new political group — former comedian and now popular activist Beppe Grillo and his Five Star Movement (M5S). The left and right coalitions in Italy are bitterly divided during this time of austerity and economic instability in the Eurozone and Grillo’s populist movement capitalized on this to garner more national attention and support than many experts expected.

While Pier Luigi Bersani’s center-left coalition was able to gain a majority in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower parliamentary house, they were unable to find the same support to control the Senate. In fact, the Senate was almost equally divided among the three different political movements, making the formation of a majority coalition a long and arduous process. Bersani’s inability to negotiate a coalition with other parties to achieve a majority in the Senate damaged his coalition and led his fellow coalition members to drive him out of their top leadership post.

President Giorgio Napolitano was set to retire after the national elections as the new members of parliament were set to choose a new president, but after five ballots that produced no clear winner as parliament refused to compromise, Napolitano agreed to stand for reelection. The President harshly criticized the parliament for failing to form a cohesive government.

With a new government finally in place, Prime Minister Letta announced an 18 month program of tasks for the parliament to accomplish. Italians can only hope that the fragile newborn ruling coalition can stay together long enough to enact change in Italy and regain its stature and some power in the European Union.