Josef A. Nothmann Journal Contributor

Faculty and administrators of the Sawyer Business School and the College of Arts and Sciences are currently debating a potential “common” undergraduate curriculum. At the same time, Suffolk seeks to enhance its international presence and profile through a variety of programs and initiatives. It is essential at this juncture that the university reaffirm its commitment to instruction in foreign language and culture for all students. Sadly this contributor suspects that foreign language programs will fall prey to financial exigencies and “strategic” decision-making. This would be a grave error.

Suffolk considers itself an international university, and the composition of its student body reflects this outlook. While geographic diversity in the student body can certainly provide some alternative perspectives for indigenous students, it is simply not sufficient in our globalized environment. An in-depth exposure to foreign languages and cultures should be considered an imperative in curriculum development. A more parochial educational model fails students both as prospective job-seekers and as citizens of the Republic.

It is not a coincidence that European students in a variety of disciplines combine their vocational or intellectual studies with a foreign language concentration. Even though English is the current lingua franca (a phrase reflective of an earlier phase of French dominance) of global commerce and education, an increasingly multipolar world demands both perspective and expertise from beyond national borders. Even within the United States a wide variety of languages are spoken. It is hard to think of a desirable job in the future economy for which fluency or proficiency in a second (or third) language would not be of significant benefit.

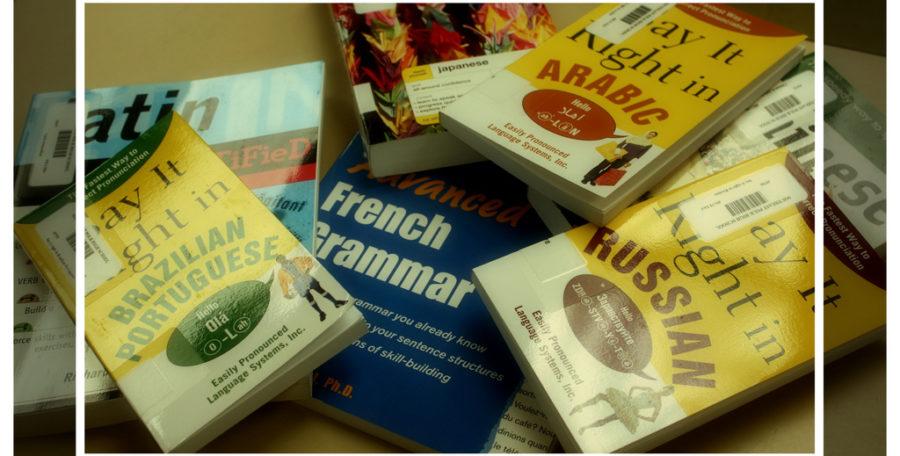

In the international sphere, the old adage remains true: trade partners will happily sell products in English, but they are much more likely to buy products from those conversant in their language and culture. In a country where the trade deficit is a topic of near constant discussion (and complaint,) a commitment to furthering commerce through language and cultural interchange seems most necessary. Instead of viewing language courses as financial liabilities, the administration should see them as investments in the future success of university alumni. Conversely, students should not view the language requirement as some chore to be checked off on the program evaluation, but rather they should leap at the opportunity to study French or Spanish or Mandarin or Arabic.

While the German program to which I am personally so attached is headed towards elimination, I hold out hope that a (re)consideration of the role of language instruction within the Suffolk model may benefit the remaining elements of World Languages and Cultural Studies. Not long ago the very concept of the university was bound to the “humanistic” model of education, for which Latin was a prerequisite and Greek highly desirable. Those days are behind us. Nevertheless, a fresh perspective and exposure to other forms of thought which linguistic study entails cannot fail to produce better workers and more cosmopolitan citizens who will do their countries and their alma mater proud.