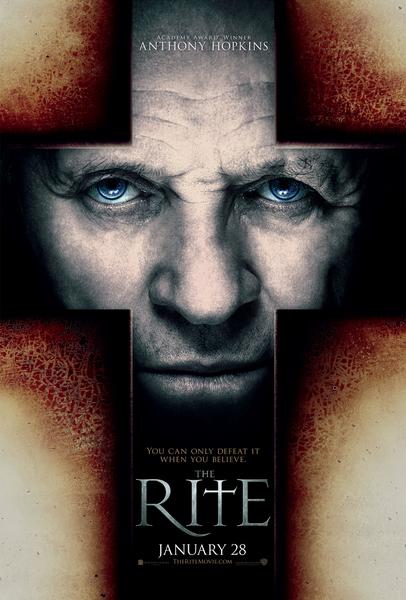

The Rite (2011, Contrafilm), which hits theaters this Friday, is the latest “horror” film from Swedish director Mikael Håfström. I went into this movie knowing only that it starred Anthony Hopkins, involved exorcism and the Vatican, and was supposedly inspired by true events. A pretty bone-chilling combination. Dr. Hannibal Lecter meets demonic possession in a creepy ancient religious setting—a foolproof equation for horror, right? Alas, I was mistaken. Along with the rest of the audience, at the screening of the film I found myself laughing aloud more than quivering with fear. The chuckling began prior to the opening credits, when the cliché disclaimer appeared on the screen informing us that what we were about to see was based on true events, followed by a quote from Pope John Paul II about how the Devil is still lurking among us today.

The story begins at the mortuary, where Michael Kovak (Colin O’Donoghue) works begrudgingly alongside his grimly religious father, following the family path that he has been condemned to. “In my family, you can only be a mortician, or a priest,” he laments to his frat-type college buddy at the beginning of the film. Apparently fed up with cadavers, Kovak chooses to go to seminary school to become a priest in spite of his lack of religious faith and his affinity for brews and miniskirt-clad bartenders. After writing an email of resignation to the Father Superior of his seminary (one of many measures taken to portray the technological savvy of the Catholic Church today), he is coerced by a priest who believes he has great potential into going to Rome for special program which teaches the ancient (here it comes) rite of exorcism. In spite of being shown several grotesque slides depicting cases of demonic possession in class, the skeptical Kovak challenges the teacher, offering intelligent psychiatric explanations for every case of so-called possession. Kovak is sent to the quirky, unorthodox Father Lucas (Hopkins), who sets out to make him a believer- for this is the only way to save him from the fate that awaits. The rest of the film is a barrage of lackluster exorcism scenes: a pregnant Italian girl who inexplicably starts speaking provocatively to Kovak in English, a possessed little boy who predicts the death of Kovak’s father, and eventually, the possession of the seemingly infallible Father Lucas himself. The behavior of the possessed is comical at best: lots of dramatic neck arching and computer-animated blue veins spreading throughout their bodies. “What’d you expect? Spinning heads and pea soup?” Father Lucas asks Kovak, though it seems more like a desperate justification to a let-down audience.

Though Kovak tries to deny the existence of the Devil, it eventually becomes impossible, as Satan seems to be stalking him specifically, appearing in the form of a mule with photo-shopped red eyes, and playing mind games with him. In what would be the climactic scene of the film, Kovak must use what he has learned to save Father Lucas, whose possession consists of his eyes turning yellow, his skin turning veiny, and he himself speaking in a goofy, senile manner, exclaiming things like “Cool dude, yeah, man!” Saving his mentor turns out to be as easy as reciting a prayer and embracing God into his life for good. Kovak tosses aside all that modern psychiatry mumbo-jumbo, disregards the fact that earlier in the film none of the other possessed victims were actually cured for good, and lives happily ever after as a priest.

At times, the film is mildly thought-provoking, raising questions concerning the place of religion in the modern world. I also enjoyed the pretty, scenic, long-shots panning over Rome. Admittedly, several loud sudden sound effects made me jump towards the beginning, but this was only until I realized that the horror I anticipated wasn’t going to come, and then they just sounded cheesy and out of place. Conceptually, the film seemed to have an interesting new take on the idea of exorcism; however, it was inhibited by its unresolved loose ends, poor writing, and oddly blatant religious propaganda. Like so many films whose fear-instilling merit relies heavily upon the presumption that the events depicted really took place, the film lacked any true horror or complexity, and ended by teaching the audience that the only way to escape the Devil is to embrace God as your savior and to hope there is a licensed exorcist near you. But I’m not worried. If the worst thing the Devil can do is turn Hannibal Lecter into a So-Cal teenager from the 90s, I’d like to know which religion I can join to ensure my protection against evil clowns.