Your donation will support the student journalists of Suffolk University. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

Revisiting history vs. removing it: Boston historians weigh in on controversial statues

March 23, 2021

As calls for racial justice ramped up last year, statues of controversial historical figures were taken down. Or, in the case of a Christopher Columbus statue in Boston, beheaded.

The six-foot white marble statue, which stood in Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park just feet away from Boston Harbor, was found decapitated in the early hours of June 10.

This wasn’t the first time the statue was defaced. It was beheaded in 2006, and the phrase “Black Lives Matter” was spray painted on it in 2015, according to the city’s official website. It has also been splattered with red paint several times by critics of the explorer.

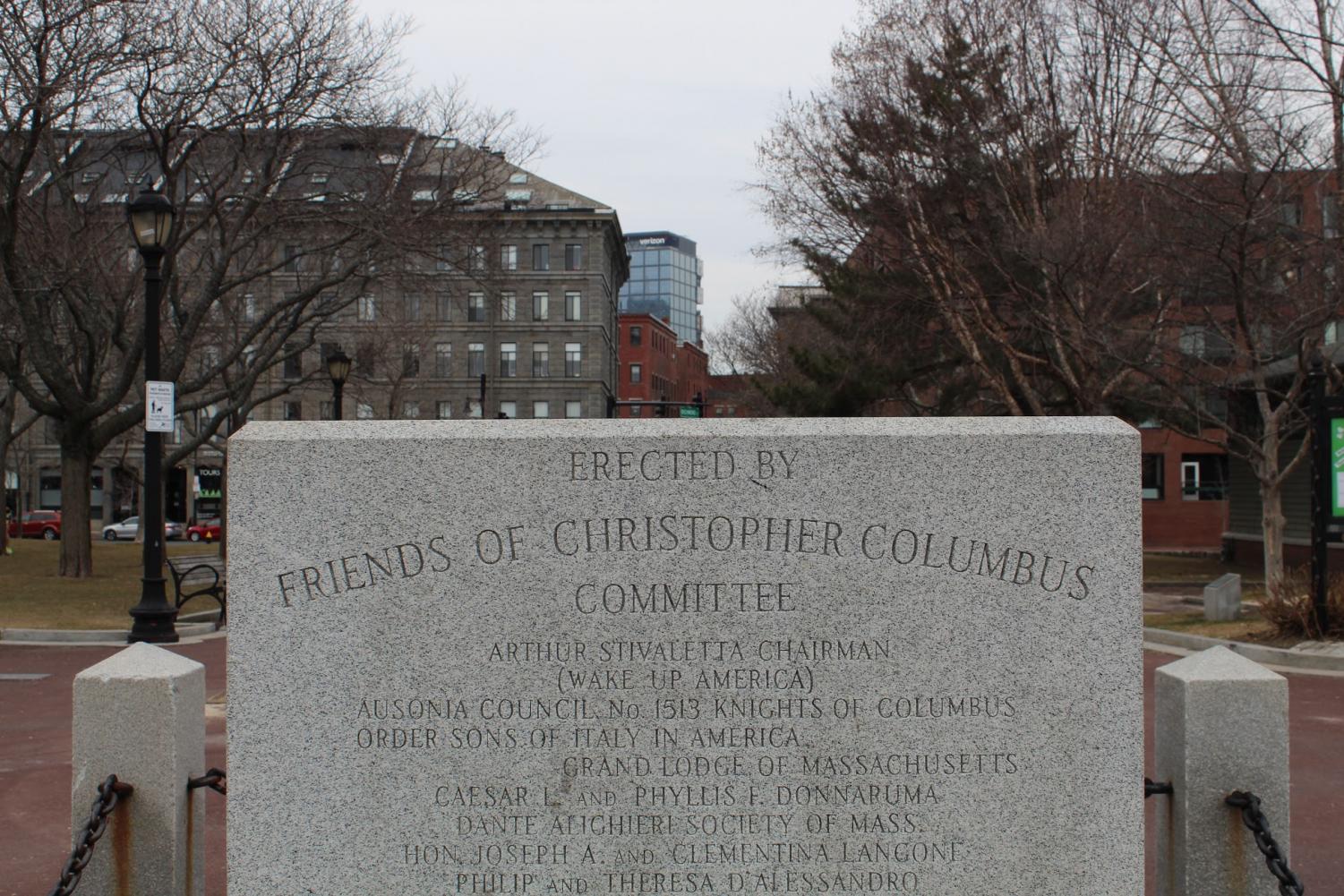

While Columbus has historically been hailed as a hero for being one of the first Europeans to settle in North America — especially by Italian Americans, who erected the statue in 1979 — he has also been criticized for his treatment of Indigenous peoples and the centuries of abuse they endured after his arrival.

“Is ‘vandalized’ really the right word here?” one Twitter user posted the morning after the statue was beheaded. “How about ‘finally removed’ or ‘public property was restored to integrity?’”

“Take that racist statue down!” another person tweeted.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh announced in October that the statue will be relocated to a development owned by the Knights of Columbus. While the dust around this sculpture has settled for now, the debate about what to do with other controversial statues in Boston still lingers.

“There has been a great percentage of sculptures that have been produced without the thought of equity…” said L’Merchie Frazier, the director of education at the Museum of African American History in Boston. “So when we look at how these sculptures came about, what ideas are invested there? That’s a part of what I see.”

Controversy in Park Square

Frazier is an artist who works to shed light on wider contexts behind Boston’s historical statues and landmarks. She designed an augmented reality project that takes students through the city and helps them understand and reimagine the works lining its streets.

One of these statues is the Emancipation Group. Erected in Park Square in 1876, this sculpture is a copy of the Freedman’s Memorial in Washington D.C. and honors President Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation.

Emancipation Group was removed in December after petitioners called for it to come down over its depiction of Archer Alexander, who emancipated himself from slavery yet was shown kneeling without a shirt at Lincoln’s feet.

“This statue has been bothering me since I was a child,” said Tory Bullock, who is Black, in a video he posted to Facebook in June. “I never really understood how messed up it was until recently, when I see everybody tearing down all these statues across the world, and I’m sitting here scratching my head like, why is this still up?”

Frazier said the teenagers who took part in her project decided Alexander should have been standing beside Lincoln while holding an American flag, since Black people fought for their freedom and “had taken the risk on themselves” to escape slavery.

“But if that sculpture is not there, and that monument is absent, how do I tell that story so vehemently? How do I represent that story in a place for students and teachers to then say ‘oh, what happened here?’” Frazier said.

Robert Allison, a history professor at Suffolk University, also disagreed with the city’s decision to remove the statue.

“I’m more in favor of putting up than taking down…” Allison said. “The thing to do is think ‘Well, who should be represented?’ not, ‘Who should we take away so that it’s less noticeable that there are people not being represented?’”

Revisiting history instead of removing it

Both historians said they would have liked to see educational markers added to the site of Emancipation Group and statues like it, rather than them being taken down. That way, signs, barcodes and other technology could help viewers easily learn about the history and controversies behind the art.

But creating equity through public art goes beyond what already exists, Frazier said. She hopes the city will focus on commissioning more statues that celebrate marginalized communities.

“When these [art] committees convene to gather information about who should be honored, what ideas should be honored and what event should be honored, all voices are important,” Frazier said. “Even people who have not been considered need to be brought up.”

Statues of women have been erected in Boston only in the last 30 years, Allison said, and most of the city’s sculptures of historical figures are of white men — many of whom are considered problematic by today’s standards.

This includes George Washington, who is depicted through a prominently displayed statue in the Boston Public Garden. While Washington was the first president of the United States and led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolution, he also owned enslaved people.

“I think anyone is problematic,” Allison said. “We all say or do outrageous things. We all will be judged by our descendants for things we did or things we didn’t do.”

Though Frazier opposed removing Emancipation Group, she said taking down certain statues can be healing.

“When I looked at the removal of Stalin in Russia, and how that came down and was such an oppressive regime that he represented… that was a great moment of unification,” she said.

Some Americans have called for statues of Confederate soldiers and generals to be removed from the south, since the Confederacy fought to preserve slavery during the Civil War.

If these statues are to come down, Frazier said she would want to see a methodology to the process. Specifically, that it would create a conversation embedded with education and justice.

That’s what she has done on Boston’s Long Wharf, where the first documented enslaved Africans arrived on Massachusetts’ shore in 1638.

The wharf is now home to the New England Aquarium, a hotel and ferry services; the only sign of its dark past being a single marker along the water’s edge that Frazier and a committee erected last year.

The marker, called “Coming in from the Sea,” is part of a national project that shows where enslaved people arrived on America’s shores. It also memorializes the 12 million kidnapped Africans who arrived in North America and the 3 million who did not survive the Middle Passage.

“We can’t bring them back, but this project is recognizing the different ports where these Africans arrived,” Frazier said. “Boston’s chance to participate in that conversation is this marker.”

The same goes for other statues around the city, she said.

“This is our opportunity to re-examine these sculptures and monuments that are in the space, and understand the big idea behind them,” Frazier said.

Check out more of Boston’s famous statues below with an interactive map.