Your donation will support the student journalists of Suffolk University. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

The “Rebecca” retrospective: Netflix’s “Rebecca” and a study in adaptation

"Everything old is new again, but new does not have to be so often indulged."

October 27, 2020

This is a ghost story. From the very beginning of Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 gothic novel “Rebecca,” the unnamed protagonist is haunted by the specter of her husband’s first wife. But in Ben Wheatley’s new Netflix movie of the same name, released Oct. 21, there’s more to the ghost than that.

After a whirlwind romance in Monte Carlo, the fresh and green Mrs. de Winter arrives with her husband Maxim to his estate of Manderley. Located squarely somewhere in the English countryside, the house is a fortress, run by the indomitable housekeeper Mrs. Danvers. The second Mrs. de Winter’s learning curve is steep, as everyone around her can’t help but compare her to Maxim’s first wife, the titular Rebecca.

No matter how director Wheatley insists his work is an adaptation of du Maurier’s novel, not a remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 Best Picture winner, it’s impossible not to compare the two. It’s ambitious, to say the very least. How ironic, that this second “Rebecca” be compared so brutally to the first.

The original adaptation is no small feat. Dame du Maurier’s novel is dense, gothic and decadent, overflowing with descriptions and feeling. Truthfully, it sometimes over-indulges in heady language and rambling observations.

But the screenwriting team of Robert E. Sherwood and Joan Harrison did an excellent job condensing the most important emotional beats of the story into a tight, snappy script; if not one that complied with the era’s censorship standards (known colloquially as the Hays Code).

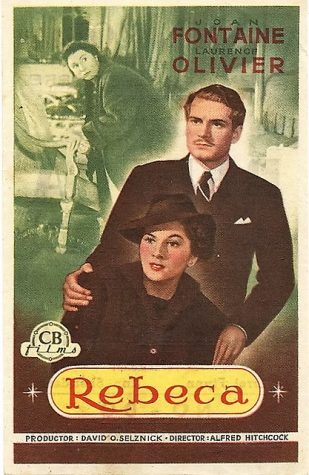

Hitchcock then added sweeping visuals and grand sets to pull Manderley off of the page as one of the iconic locations in the cinematic canon. It cannot be overstated how well Hitchcock’s “Rebecca” works on every possible level, from superproducer David O. Selznick, to actors Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine, to black-and-white cinematographer George Barnes.

It’s the great master of suspense’s one and only Academy Award for Best Picture winner in an oeuvre stuffed to bursting with iconic films.

All that being said, it’s hard for another, deeply modern film to compete. Wheatley and his own cinematographer, Laurie Rose, throw all elegance to the wind, creating an utterly sunlit film, made for streaming sensibilities.

This is just one of many choices that undermine the moody, unfamiliar atmosphere the story is so famous for. The estate doesn’t feel empty and imposing with an army of servants running around like a Downton Abbey Christmas special.

Character moments and dynamics are introduced then left to hand. Editing choices are unmotivated, dream sequences are poorly shot and there are some truly puzzling music choices; who told Wheatley that cloying modern folk music fits this tone?

Even lead actress Lily James, who by all accounts is very good in the rest of her work, comes off as barely suitable in this film. Her onscreen husband Armie Hammer fares even worse in the role of Maxim de Winter, a volatile man made all the more unlikable due to uneven acting choices that were surely the product of actor and director.

Kristin Scott Thomas tries her best with the steely politeness of Mrs. Danvers, who was played in 1940 by Judith Anderson, but even her pitch-perfect casting can’t make up for what lacks in the writing.

Screenwriters Jane Goldman, Anna Waterhouse and Joe Shrapnel were in a unique position while readapting “Rebecca,” with the opportunity to explore circumstances and subjects that weren’t permissible under Hays-era censors.

Instead they added a number of modern anachronisms, a frenzied masquerade ball, for example, while completely ignoring queer themes that could only be subtext in 1938 and 1940.

Everything old is new again, but new does not have to be so often indulged. Skip Netflix’s latest offering and seek out one of Hitchcock’s best. It hasn’t aged a day.

“Rebecca” (2020) is available to stream on Netflix everywhere. “Rebecca” (1940) is available in full to stream on YouTube.

Follow Emily on Twitter @emily_sorano.