Your donation will support the student journalists of Suffolk University. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

Congestion pricing could solve Boston’s infamous traffic problem

April 10, 2019

As New York City follows through with their plan to establish the traffic reduction policy called congestion pricing, Boston is still unwilling to move forward with this proven path for change.

Congestion pricing is a method of deterring drivers during peak commuting times by tolling drivers as they enter a certain part of the city. New York’s plan proposes a toll that would amount to around $11 a day for most drivers to enter Manhattan below 60th Street, according to The Boston Globe.

This new method of controlling traffic at peak times is meant to reduce drivers’ carbon footprints in the city, relieve gridlock and provide billions of dollars towards the city that could be allocated to improving their public transit system; all of which are traffic symptoms that are not unique to New York, and are issues that Boston has tried and mostly failed to tackle in the last several decades.

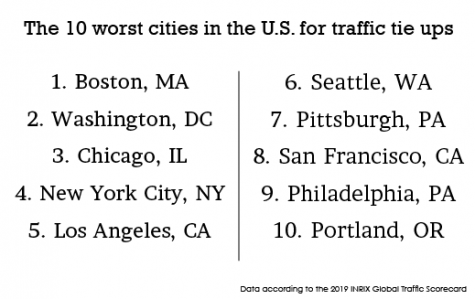

The reasons for Boston’s slow response to downtown congestion are unclear, especially with the knowledge that the city recently rose above New York as the No. 1 ranked American city for traffic congestion, according to a transportation analysis firm INRIX.

The same firm reported that the average commuter in Boston is estimated to spend 164 hours a year stuck in mind-numbing gridlock, which is estimated to cost drivers $2,291 annually. The cost of this inconvenience both in time and money eats into the slim budgets of many drivers, and needs to be addressed.

Although congestion pricing also imposes a cost onto the driver, it does so at a price that is expected to be far less than the hidden cost of sitting in traffic every day. In addition to this, the policy would encourage drivers to travel using public transit systems at a lower cost than driving would be, only further reducing the economic pressure placed on drivers.

Many people travel using their privately-owned vehicles for comfort purposes with the idea that it will ultimately save more time than taking public transportation. However, despite any attempts on the individual level to avoid traffic, congestion is still inevitable, especially during peak rush hour times.

As long as the roads are free, there will be no disincentive to drive into the city. Boston has made prior attempts to lighten up traffic congestion through the decades-long Big Dig project which was completed in 2006.

The project was extremely costly, and while it did reduce some congestion in the short term, there has still been a recurring demand for the use of the highways. The less traffic that exists, the more people will want to drive into the city, which ultimately leads to an increased buildup of traffic in the long-term.

Boston’s MBTA system is widely criticized for being slow, which often encourages individuals to drive into the city in order to avoid train delays. However, with the introduction of congestion pricing, money generated from the policy could be used to improve the functioning of Boston’s public transportation system.

In addition to improving the MBTA, congestion pricing will also significantly reduce carbon emissions within the city of Boston. This will help the city to achieve its sustainability goals for the future, and will also improve the quality of public health in the long-term for Boston residents.

The policy is not a new concept; London put a similar plan in place in 2003 that has since reduced congestion by 15 percent and increased traffic speeds by 30 percent, all while reducing the economic load on drivers and increasing the air quality of the city, according to the Transport for London.

London was the first step in proving the effectiveness of congestion pricing, and New York is likely to be the second piece of evidence in its favor. If Boston does not implement this change soon, the plague of traffic is likely to continue to spread, and our public transit will not be able to save us.