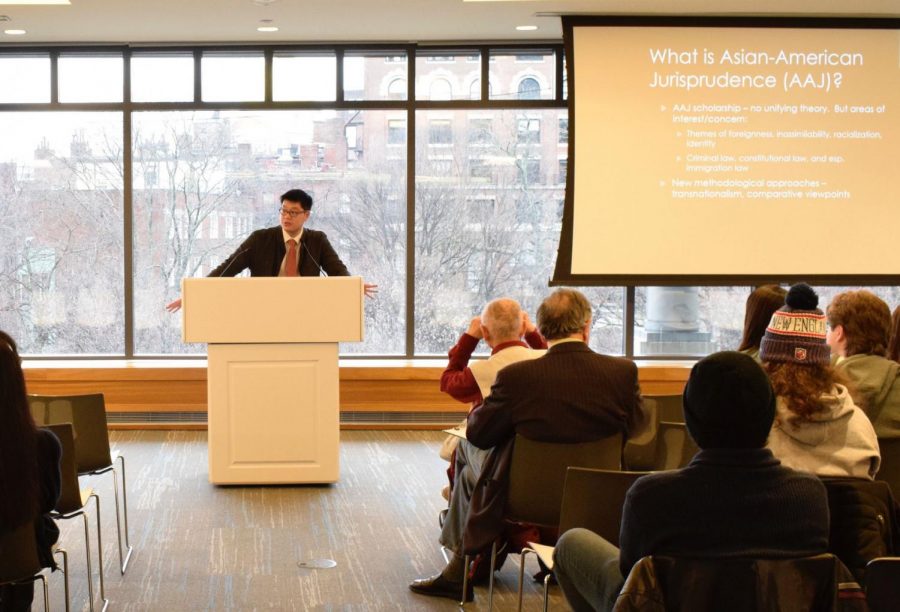

Associate Professor of Peking University School of Transnational Law and researcher of the Asian-American Jurisprudence (AAJ) scholarship Norman P. Ho, took stage at the lecture “Chinese Nationality Laws & Asian-American Identity” on Wednesday, Feb. 7, presented by Asian Pacific American Law Students Association.

“Born and raised in America, there are questions,” Ho said. “Am I American? Am I more Chinese? Am I more Taiwanese?”

In the United States, Ho explained, Chinese-American identity has a twilight zone that is “tug-of-war between Americanization and Sinicization.”

Asian-American citizens are not fully treated as Americans. They face an expectation to be Chinese by Chinese or Taiwanese citizens. In the lecture, Ho explained how Asian-Americans feel pressured to uphold the societal norms, culture and language based on the foreign law of their ancestral home country.

The lecture outlined how Chinese-Americans are treated by Chinese society and nationality laws.

“Born in America, went to university in America, outstanding in English and you travel to your ancestor home country. And all the time you would face is discrimination,” said Ho. “For many Asian-Americans and Chinese-Americans, when they go to their ancestor home country, socially and culturally, they are treated simply as Chinese, not American.”

Asian-American identity is shaped by social attitude in their ancestral home country. Chinese people have the social expectation of Chinese Americans that they should be more loyal to China.

According to the case studies by AAJ in China, Chinese-Americans cannot get jobs for foreigners. For example, a Chinese-American who applies for a job as an English teacher may be denied because their Asian appearance.

“When the English teaching school sees that you have a Chinese face, they see you are fully Chinese not really American. They deny you employment,” said Ho.

Ho shared his personal experience volunteering as an English teacher in China.

“When I had an interview and I showed up, the officer of the school said ‘What, you are Chinese!’” he said. “I had to explain that I am ethnic Chinese, but I am American and English is my native language. In the end, I was not hired.”

Because the school was looking for foreign teacher, Ho was not hired at first. Eventually, he got accepted to the position and met with the other teachers who were hired.

“I met the other foreign teachers. All white,” said Ho. “Two of them were Russian who did not speak English very well. One of them was French who had a very very heavy French accent.The point is English is not a primary concern with [Chinese society], rather optics.”

Ho mentioned discrimination between the salaries of western English teachers and Asian-American English teachers in China and Taiwan. Asian-American teachers were paid $14 per hour while teachers that were American citizens were paid $20. For this issue, many Chinese-Americans teaching in Taiwan founded an organization to claim this discrimination.

“Social treatment of Asian Americans is also enforced by law,” Ho said. Chinese and Taiwanese law treat Asian-Americans as nationals and expect them to remove their American nationality and identify Chinese or Taiwanese nationality.

The nationality law in Taiwan, according to the Republic of China Nationality Act, recognizes an individual as a Taiwan national even if they were not born in Taiwan.

“Even if you were born in the U.S. and your mother or father was a national of Taiwan at the time you were born, you are automatically considered a Taiwanese national,” said Ho.

Chinese law is similar. Under Chinese law, an individual is a Chinese national if they are born abroad and their parents are Chinese nationals, according to Article IV of the Nationality Law of the People’s Republic of China.

“If two Chinese nationals go to the United States and have a kid there, he will have American citizenship at birth,” said Ho. “If his parents have not settled abroad, he will be seen by China as Chinese nationals – not American. “

So long as a Chinese-American’s parents have not settled abroad, or acquired citizenship in another foreign country, that person will be considered a national of China rather than an American citizen by China itself.

“Chinese-Americans who have never stepped foot in China may automatically be considered nationals of China,” said Ho. “American citizens are detained and not allowed to leave the country, despite being the American citizens.”

According to Ho, China has said “we don’t consider them as Americans because they are Chinese nationals. So we don’t let them leave this country.”

“China does not recognize dual nationality for Chinese citizens. A Chinese citizen that acquires foreign citizenship of his own free will automatically lose Chinese citizenship,” said Ho.

According to the Act IX of the law, “Any Chinese national who has settled abroad and who has been nationalized as a foreign national or has acquired foreign nationality of his own free will shall automatically lose their nationality.”

However, despite being born and raised in the U.S. and not having spent any significant time in East Asia, Asian-Americans have experienced racism, and, more specifically, have been perceived as Chinese not American.

Suffolk University Professor of Asian Studies Ronald Suleski discussed the lecture in an interview with The Suffolk Journal.

“I was very pleased to hear Dr. Ho talk in such a normal way and convincing way,” said Suleski. “I thought that nationality law and personal identity were two different things. Many people have to struggle with what their identity is, what their citizenship is, what their country is, and who they are.”

Suleski explained that it is always important to be aware of people’s backgrounds and to not make assumptions about where they come from.

“One thing that I try very hard in my life and in my classes is to be completely acceptable of everybody. In my classes, there are all kinds of students who have all kinds of backgrounds,” said Suleski. “I try not to say ‘we,’ because ‘we’ has to be all of us. I try to make sure that what I say is respectful to all of the people and does not exclude anyone.”

Ho is hopeful that doing research like this can help improve the lives of Asian-Americans.

“One hope I have is that I want to bring more attention to the kinds of struggles and challenges that Asian-Americans face on a daily basis,” said Ho in an interview with The Suffolk Journal. “I want people to see not only the Asian-Americans struggles and challenges in America, but also some of them are facing challenges in their ancestor home countries. One goals of this research is to improve the situation for Asian-Americans.”